|

By Connor Bennet Hypothesis If people associate with a higher scale of income, then they are more likely to consider the country to be run very democratically. Null There is no relationship between, or a lack of data to represent, a persons associated level of income and their opinion of how democratically the country is being governed. Related Scholarly Works James Avery's writing,“Does Who Votes Matter? Income Bias in Voter Turnout and Economic Inequality in the American States from 1980 to 2010”, contributes to my research by highlighting the changes to our political arena over the last three decades. Much evidence has been gathered on the rising inequality of voters, and the disparity in representation that low income citizens receive in the political process (Avery, 2015). The ways in which the public can participate in the democratic process rely heavily on their economic advantages (Avery, 2015). Most notably, people of a higher economic class are more able to contribute income toward campaigns and special interest groups, while people of a lower economic status are less capable of using incomes to further their political preferences (Avery, 2015). The article provides insight to why people may consider the country being run more democratically when they associate with a higher socioeconomic status. Daniel Laurison's work,“The Willingness to State an Opinion: Inequality, Don’t Know Responses, and Political Participation”, uncovers the relationship between individuals' economic status, their responses to political surveys, and their likelihood of voting. The author found that lower income individuals are more reluctant to express political opinions (Laurison, 2015). It is also found that participants who provide "Don't know" answers on surveys are far less likely to participate in voting (Laurison, 2015). The author contributes these factors to income. It's found that income leads to high levels of participation by increasing ones ability to understand and engage in politics, as well as enhancing ones sense of self to construct political opinions (Laurison, 2015). From the reading it could be understood that individuals of lower incomes feel detached from the political arena and are then less likely to become involved (Laurison, 2015). If people of a lower economic status tend to not associate in democratic processes then it is logical to predict that income plays a substantial role in how democratically one thinks the country is being governed. Importance As inequality in United States, and elsewhere, continues to rise, it is crucial to the foundation of democratic qualities that we have a participatory voting population that is in agreement with how the institution is being run. If income is a determinate of how people view democracy, then the system is broken. Rather than being influenced by the people, it would seem that the institution it is truly only being driven by the select few fortunate enough to attain a higher socioeconomic status. Measurement The variables chosen in my regression were scale of incomes, and how democratically the respondent felt the country was being governed. Both variables were gathered from the World Value Survey using 2011 United States survey respondents. In the questionnaire, both variables were assigned a sliding scale of one to ten with one being not at all democratic and the lowest income level, and 10 being completely democratic and the highest level of income. The independent variable, scale of incomes, is a subjective measurement that does not assign real values to its question. This leaves respondents to choose where exactly they feel they belong within society without being broken into specific income brackets. The dependent variable, how democratically the country is being governed, was chosen for its ability to show the approval of the current political structure. Comparing the two variables would show whether there is any correlation between income and democratic approval. Data Findings

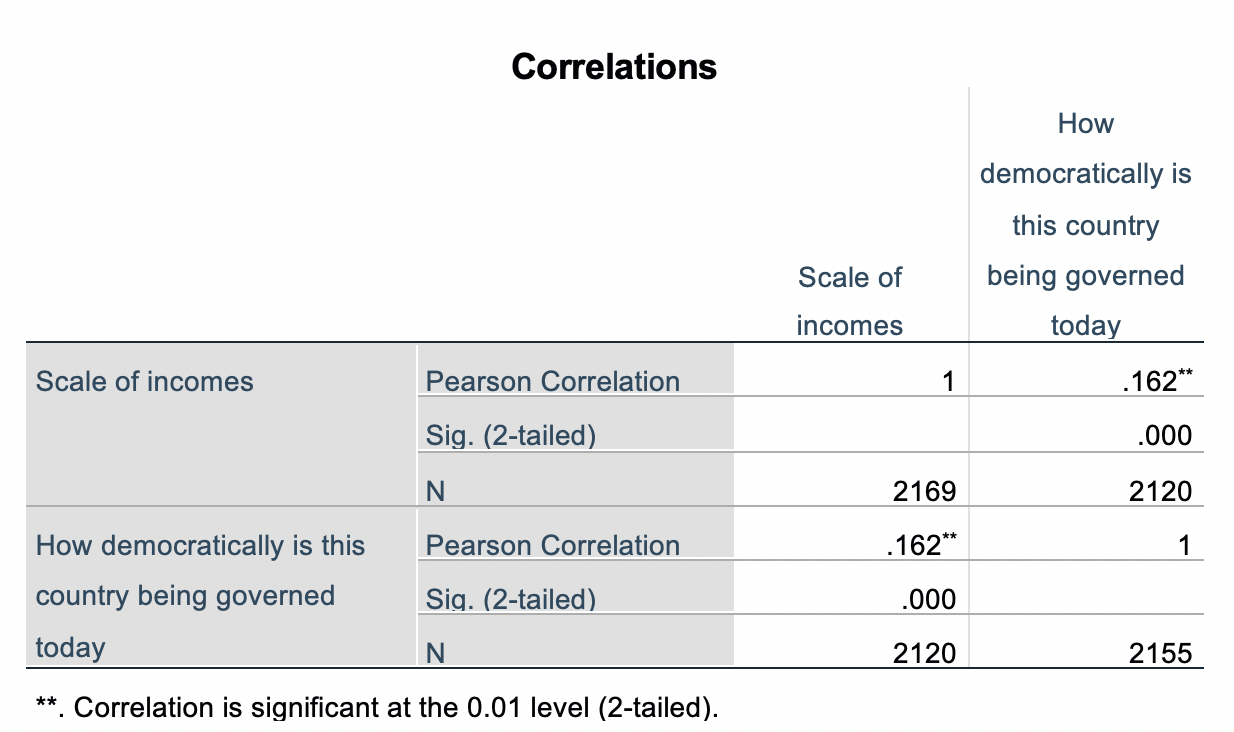

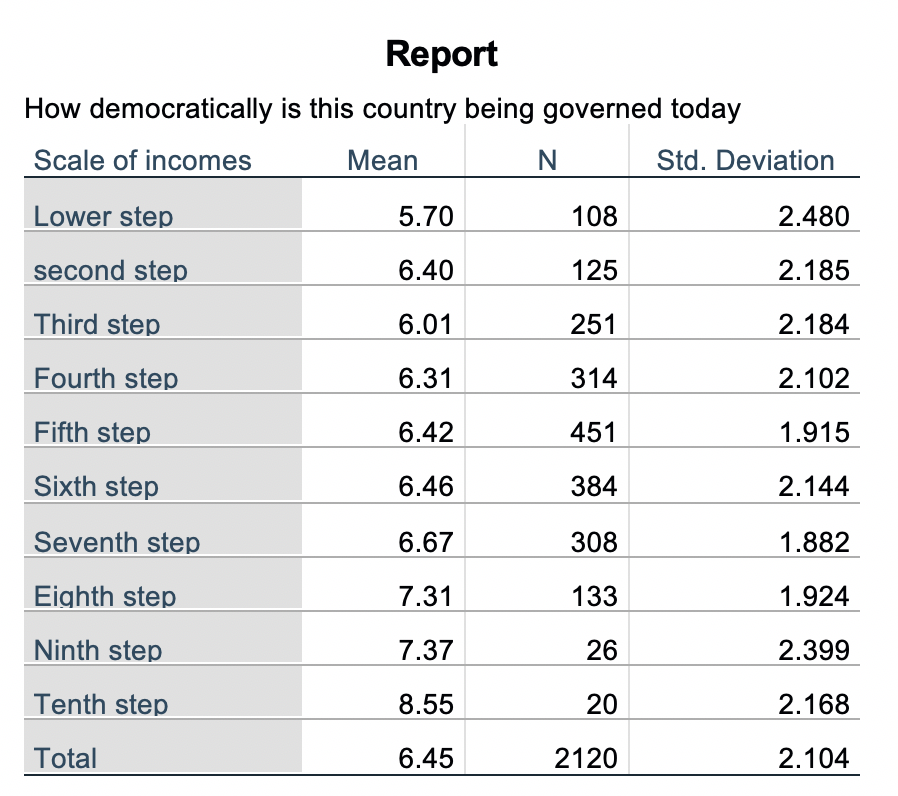

After running a difference of means and regression on the variables I came up with a positive correlation of .162** and statistically significant p-value < .05. In the difference of means it is seen that the average respondent increases the value of how democratically they feel the country is being governed as their scale of income increases. With this finding, I am able to reject the null hypothesis and show a positive correlation between a respondents income and how democratically they view their country. The subjectivety of income scales without specified numbers could have been a factor in the outcome if this data. In doing further research I would like to compare responses with specified income brackets to determine if peoples perception of wealth are greater or lower than what they truly are. If this is the case then the data may be representing a correlation of other social and physiological variables rather than income. Works Cited

0 Comments

By: Annie Farrell

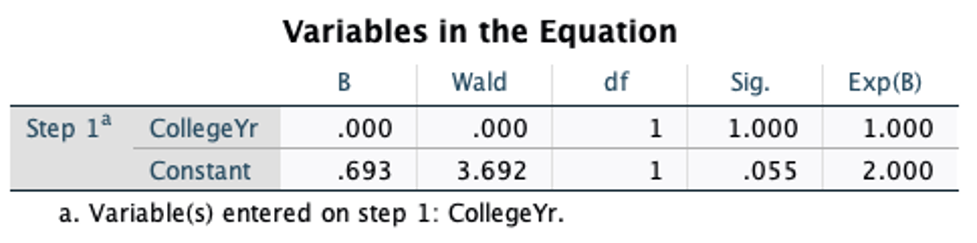

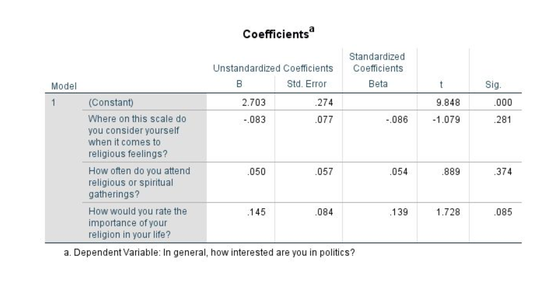

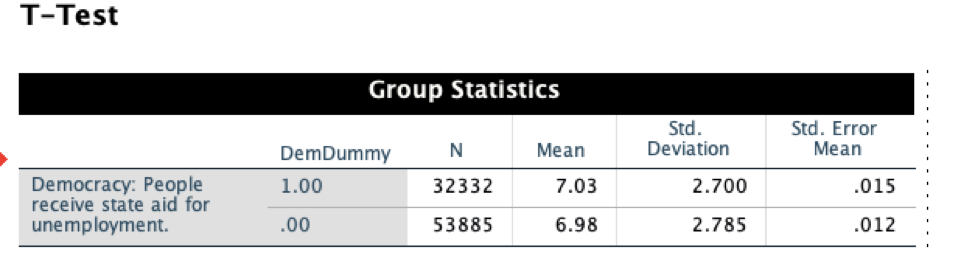

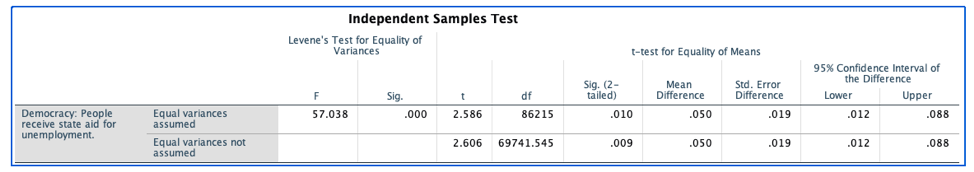

Hypotheses and motivation My hypothesis test focuses on the potential positive correlation between civic engagement and religious tendencies of the youth. Young people have historically been one of the lowest groups in terms of voter turnout percentage, resulting in numerous organizations focused on changing that very fact. If it is found that young people involved in religious practices are more likely to participate in democracy, then it is possible to implement strategies within these organizations that are more likely to increase civic engagement among the youth. These strategies would not mean imposing religious events or ideologies on young people. Viable strategies could include isolating the causal mechanism and incorporating it into organizational events, for example, events that encourage young people to become more involved in their local communities. Discovering causes behind why young people do or do not vote has the possibly to mobilize the entire group. My hypothesis is as follows: religious involvement/tendencies contribute to a higher level of civic participation. My independent variable is religious tendencies while civic engagement is my dependent variable. My null hypothesis is that there is no correlation between religious involvement and civic participation. I leave my variables somewhat vague in my hypothesis as I am testing different questions that do not follow a clear definitive definition throughout. For example, I test questions such as “are you registered to vote?” and “how involved do you consider yourself in politics?” with “have you attended a religious service?” and “how important is religion in your life?”, questions that all have slightly different denotative meanings. The causal mechanism behind my hypothesis is that religious persons are more prone to be politically involved as a means of making a positive change in society. I will discuss this concept as a causal mechanism in more detail when explaining previous studies. In the first study “Love of God and Neighbor: Religion and Volunteer Service among College Students”, Elizabeth Ozorak tests for a correlation between religious college students and volunteer service. She finds that belief in God is a strong indicator for participation in volunteer service for men especially (Ozorak, 2003). However, there was still a correlation between belief in God and aiding the community. She states that the casual mechanism behind this phenomenon is that “religion is a strong source of the kind of moral identity that motivates helping behavior on a regular basis” (Ozorak, 2003). The next study which tested my same hypothesis, “Religion and Civic Engagement Among America’s Youth”, concludes similar findings. Gibson also finds that likelihood of volunteer participation is strongly correlated with degree of religious tendencies in American youth (Gibson, 2008). Yet, when testing for civic engagement a strong relation was not found. This raises the question if any identity trait whatsoever will influence the youth to vote and be politically involved. This hypothesis test is important as it can potentially answer the question of why young voters do or do not vote. Additionally, although my question is very similar to the studies I discussed previously, mine does not focus on a particular religious group leaving room for students who may identify as spiritual but do not follow an organized religion. Description of concepts, data, and measurement For my analysis I utilized five different questions from the 2018 PAL data set. The 2018 PAL data set was collected by last year’s Political Analysis Lab in order to help test various hypotheses related to college age students. The data is divided between two main groups, the first being Fort Lewis College students that the class sampled themselves, and the second from a randomized representative group of participants from Qualtrics, a survey software platform. The questions that I used for my research are as followed: “where on this scale do you consider yourself when it comes to religious feelings?”, “how often do you attend religious or spiritual gatherings?”, “how would you rate the importance of religion in your life?”, “in general, how interested are you in politics?” and lastly “are you registered to vote?”. My variables are religious tendencies/involvement and civic engagement. I use the three questions on religious tendencies as they fully capture any degree of religious or spiritual feelings instead of organized groups. For my second piece, civic involvement, I included the one question on being registered to vote and the other on general interest in politics. Being registered to vote is not always a clear predictor of actually voting or being civically engaged. Additionally, being interested in politics does not always correlate with likelihood of voting. I included these two to hopefully fully encompass an appropriate degree of political involvement. Fortunately because I am using the 2018 PAL data, everything I will be using has already been cleaned. My questions regarding political involvement are counted on a three-point scale for “are you registered to vote?”, and a four-point scale for “how interested are you in politics?”. For my other questions, they utilize a four, five and six point scale and typically range from very religious to not at all religious in order to keep means consistent. Presentation of analysis and results For my data analysis I ran one bivariate correlation and two linear regressions. I started with the bivariate correlation between the responses to “in general how interested are you in politics?” and “where on this scale do you consider yourself when it comes to religious feelings?”. A bivariate correlation tests the strength of the correlation between the two variables. I thought this would be a beneficial test to begin with my analysis with as it would quickly show if there is a correlation. As seen in Figure 1 my Pearson correlation is -.008 meaning there is essentially no relationship between my two variables. Additionally, the Pearson correlation is negative meaning that if anything the opposite effect is occurring. The Sig. (2-tailed) number is .878 meaning there is no statistically significant correlation as it far exceeds .05. If I were to base my hypothesis off this test alone, I would have to fail to reject my null hypothesis. Next, I ran two linear regressions. I chose to use linear regressions for this portion of my data analysis as I can compare one variable to others simultaneously. I compared my two questions on political involvement to all of my questions on religious tendencies. For my first test, I used the question “in general, how interested are you in politics?” As my dependent variable. Two of my Sig. numbers for this test were .281 and .374, far above the necessary value to be considered statistically significant. When translated, this means that there is a 28.1% and 37.4% chance respectively that I made a type I error. Because of this, for these two questions I would have to fail to reject my null hypothesis. However, for one of my questions “how would you rate the importance of religion in your life?” my Sig. number was .085, which although does not meet the criteria for being statistically significant is fairly close. This means that there is only an 8.5% chance that I made a type I error, because of this I can neither fully reject or fail to reject my null hypothesis as this data is suggestive of a correlation. For my beta coefficient, it was negative -.083 for “where on this scale do you consider yourself when it comes to religious feelings?”, meaning that in this case there is a very slight decrease in interest in politics when a person ranks higher on this scale. My other two beta coefficient values were simply a slight increase. For my second linear regression, I compared the same religious tendency variables with the responses to “are you registered to vote”. For my second linear regression my Sig. values were .340, .029 and .104 respectively. Similar to the first test, there is a 34% chance I made a Type I error meaning on this question there is not a notable statistical significance. However, my second two values are notably lower being a 2.9% and 10.4% chance I committed a Type I error. Although significant p-values are sometimes higher than .05, my .104 Sig. value is not low enough to suggest a correlation between the two variables. Lastly, for my question “how often do you attend religious or spiritual gatherings?”, my Sig. value was statistically significant as it was far below the .05 standard. If this was my sole test I would have to reject my null hypothesis. It is important to note that because I am measuring closely related concepts, there is a chance my Sig. values are lower than they would have been if analyzing one at a time. Additionally, my sample size is relatively small which may have also inflated my p-values. For my beta coefficient, the same pattern followed again with my first variable being negative and my second two as positive. After reviewing the analysis, there is suggestive evidence that a correlation between religious tendencies and civic engagement is prevalent in regards to some variables presented. At the same time there is not overwhelming statistical significance in any of my tests that would lead me to confidently declare a correlation considering potential statistical errors. Future research should be focused on questions like “the importance of religion in your life” and “how often do you attend religious gatherings?”, as those were the most suggestive of a relationship. The nature of the results may relate to the degree of religious commitment in ones daily life. Although the first question also pertains to the extent of religious devotion, the phrasing “religious feelings” may have confused some participants. Moving forward I would suggest tests that only involve participants who consider themselves “strongly” or “very” religious”. Gibson, T. (2008). Religion and Civic Engagement Among America’s Youth. The Social Science Journal. Vol. 45. pp. 504-514. Ozorak, W., E. (2003). Love of God and Neighbor: Religion and Volunteer Service among College Students. Review of Religious Research. Vol 44. Multi-National Analysis of State Sponsored Unemployment Aid as Characteristics of Democracy.11/22/2019 By James Summers Throughout history there has been a notion within the United States that Democratic states and Autocratic states are stratified in a hierarchy in which Democratic states are superior to Autocratic states. This study seeks to situate itself to try and show if receiving state aid even lends to the idea of any differences in Democratic and Autocratic countries. This research will operate with the following parameters: Hypothesis: Receiving state aid for unemployment will be a necessary condition to be living in a democratic state. Null: receiving state aid for unemployment has no relation to living in a democratic state. IV: Receiving state aid for unemployment DV: Living in a Democratic or Autocratic state Causal Mechanism: Living in a Democratic country contributes to higher levels of State sponsored aid being held as essential of Democracies. Comparative studies from Sergio Espuela and Youngho Cho test comparative analyses of Dictatorships and Democracies that reveal some of result the dichotomous relationship of these regime types. In Sergio Espuelas’ study he looked at Dictatorships and if they are less redistributive than non- dictatorships. His study looked at countries that were currently dictatorships and evaluated their past regime types to see if being a dictatorship hampered social program spending. Some of the countries had regimes that carried over the four year period that changed from democracy to autocracy’s. What Espuelas found was that dictatorships were less generous in social spending than democracies.[1] This is one conversation that looks how Democracies and Autocracies differ on social policy looking at economic spending. Another study by Youngho Cho uses data from the World Value Survey to understand the support for democracies looking at states that are democracies and those that used to be non-democratic.[2] Both studies use a multi-national comparative analysis in trying to understand social policy spending and democratic support in democratic and non-democratic states. This is important because multi-national analysis helps to understand general trends happening around the world. Description of concepts, data, and measurement: My independent variable was measuring the idea of people who receive state aid for unemployment as an essential or non-essential condition for living in a democratic state. However I needed a definition for autocratic states and democratic states. I used data from the non-governmental organization Freedom House whose data denotes countries as “free” and “not free”.[3] I used this designation to find autocratic states and democratic states and create a dummy variable that will help to discern from the other. The new variable codes democratic states as “free” states and has a numeric value of 1. Autocratic states are coded as “not free” states and have a numeric value of 0. My dependent variable that is being tested is which country the respondent is living in at the time of their responses. My null hypothesis will help to determine if there is or is not a relationship between receiving state aid for unemployment and that being a condition of living in a democratic state. This recoding of data was a part of my larger data set that came from the World Value Survey. The World Value Survey studies the changes in values and their impact on social and political life around the globe. This is where the question about receiving state aid for unemployment as a characteristic of democracy and the data that was surveyed came from.[4] The question is scaled from 1 to 10 with 1 “being a not essential characteristic of a Democracy” and 10 being “an essential characteristic of Democracy”. This data is useful because it has a larger response population that allows for greater accuracy rather than one respondent from one country and analyzing based off of that. Presentation of analysis and results: In order to get results from this data I ran a comparative means Independent-Samples T Test to see if there was any significance between respondents in Autocratic and Democratic countries and receiving unemployment aid as "essential" or "non-essential" to living in a Democratic state. In the “independent samples test” chart in the column sig. (2- tailed), the results are .010 and .009. What this means is that if looking at a normal distribution chart at the ends of each side, or tail, the confidence level or either tail falls within .025 threshold for any significance to reject the null hypothesis. Another figure of importance on this chart is the column of significance, of sig., the p-value of this test is .001. Which means that the threshold for statistical significance of .05 has been met and there is a 99% confidence interval to reject the null hypothesis. The “Group Statistics” chart is important because it puts into perspective the Error Bar visual graph. The dependent variable on the x-axis is the democratic or non-democratic state respondents live in. The y-axis is the independent variable looking at state unemployment aid as a characteristic of a democracy. The Error Bar visualizes the error or uncertainty based off of the variables ran in the T Test. The length of the Error Bars, or lack thereof, reveals the uncertainty of the data point. These short bars show that the values are concentrated and reliable. However, when looking at the “Group Statistics” chart the number of respondents (N) is roughly 96,000 and difference in mean from “free” and “not free” states is .05 which means that the averages for both sides are not as large as the numerical values would have us believe. There is no overlap between “free” and “not free” Error Bars which is slight but still present still giving some statistical significance to the tests ran. Overall the T Tests and the Error Bar graph give us confidence to reject the null hypothesis and that receiving state aid for unemployment is a necessary condition to be living in a democratic state. This study correlates to democratic efficacy because that data shows that Democracies have a this leg up when it comes to state sponsored aid how that is an essential characteristic of Democracy. Sources [1] Sergio Espuelas, "Are Dictatorships Less Redistributive? A Comparative Analysis of Social Spending in Europe, 1950-1980." European Review of Economic History 16, no. 2 (2012): 211-32. www.jstor.org/stable/41708657. [2] Youngho Cho, "To Know Democracy Is to Love It: A Cross-National Analysis of Democratic Understanding and Political Support for Democracy." Political Research Quarterly 67, no. 3 (2014): 478-88. www.jstor.org/stable/24371886. [3] “Freedom in the World 2018: Democracy in Crisis”, accessed Nov. 19, 2019, https://freedomhouse.org/. [4] World Value Survey “Who We Are,” accessed Nov. 22, 2019, http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp By Katherine Potter Hypothesis and Motivation:

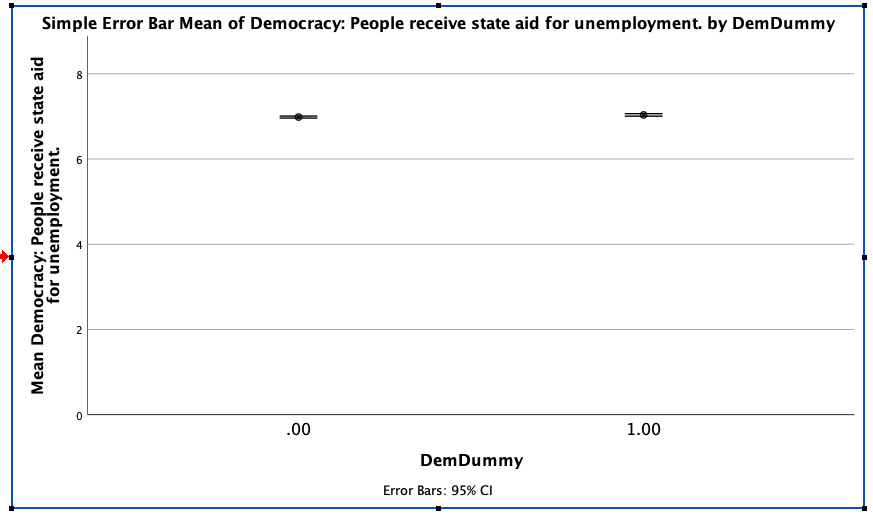

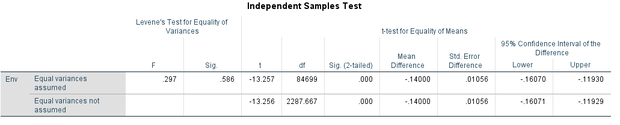

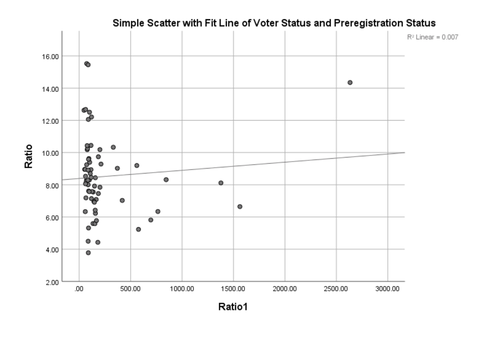

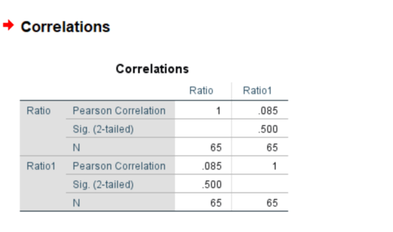

Environmental and economic agendas within the United States express great potential for congruency and mutual benefit; however, a common misconception exists positing that only one may prevail over the other. Understanding environmental attitudes within the US, especially how they are impacted by desire for economic growth, is crucial for gauging the efficacy of democracy. This research will operate with the following parameters: Hypothesis: The United States will express greater value of economic growth and less for the environment when compared to other states. Null Hypothesis: There is no correlation between a specific country and citizen value of either environmental protection or economic growth. IV: Environmental protection vs economic growth as prioritized value. DV: The country these values are measured in (US vs all other countries). Causal Mechanism: Efficacy of democracy or a given country contributes to stronger valuation of environmental protection. Existing data suggest that there are complex relationships between economic and environmental attitudes. Multiple studies have found that people displaying environmentally conscious priorities have altered their consumer habits and values, exerting large impacts on economic elements (Polonsky, 2012, p. 242-3). Scholar, Lori M. Hunter, also conducted an analysis of existing environmental data collected from the 1993 World Values Survey in which she compared environmental perceptions among native-born and foreign-born people within the US. It is concluded that concern for environmental issues is transnational but highly contingent on national contexts (Hunter, 2000, p. 576). Similarly, the data used to complete this research is the environmental module from 2010-2014 World Values Survey data. These studies engrain why this research matters because they support the notion that proper investigation of US perceptions of the environment and economy are critical for furthering progress on both fronts and is essential in addressing perceptions of the efficacy of democracy. Description of concepts, data, and measurement: The independent variable, “environmental protection vs economic growth,” was recoded so a response valuing environmental protection over economic growth is 1, responses valuing economic growth more are assigned 0, responses that were unsure are 0.5, and any other category is assigned as “system missing.” These recoding steps were completed so the desired measurement and response of stronger valuation of environmental protection accounted for a larger number in the means test, as opposed to responses which value economic growth more. Respondents who were unsure about their values were assigned a value directly in the middle of either side in order to acquire a more accurate depiction and analysis of existing means. Since this analysis aims to contrast environmental and economic attitudes within the United States as opposed to other states, the dataset was recoded to isolate the United States from the rest. This result was achieved by coding the US country code of 840 as the numeric value 1 while coding every other country included as 0. Every result emerging from the US is evidenced by their assigned value of 1 and rendered easier to interpret. Presentation of analysis and results: This graph displays the results of a simple means analysis with the y-axis as the independent variable or economic and environmental perceptions, while the x-axis is the dependent variable with the US marked on the right and the rest of the countries on the left. The final graph was achieved through constructing a bar chart with the two aforementioned variables in their respective positions but specifying that only the mean data is displayed for the independent variable. Analysis proceeded by comparing means through independent sample t-tests. Each of these groups were defined according to the previously noted numerical assignments and further analysis proceeded. Due to how the dataset was recoded to provide environmental values with 1 and economic values with 0; the mean depicted on the left for all other countries displays a more significant emphasis on environmental values than the mean depicted on the right for the US, showing a higher emphasis for economic values. This means that, when compared to the rest of the world, the US has weaker regard and lower value placed upon the environment (Figure 1). Shown below (Figure 2) is a .586 significance p-value for the equality of variances test, indicating that there is no statistically significant correlation between the variables. The 2-tailed significance depicted within the t-test for equality of means is .000 for when equal variances are assumed and when they are not. Because this p-value is so small, it indicates statistical significance and encourages rejection of the null. The results from this hypothesis test have significant implications for the original hypothesis. Since it was initially predicted that the United States would display weaker emphasis on environmental protection when compared to economic growth, it is supported by the data presented within this specific analysis. Consequently, the null can be rejected, and it can be inferred that the relationship between environmental or economic values are related to country-wide contexts, including the efficacy of democracy. Hunter, L. M. (2000). A comparison of the environmental attitudes, concern, and behaviors of native-born and foreign-born U.S. residents. Population and Environment, 21(6), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02436772 Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.). 2014. World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Datafile Version: www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute. Polonsky, Michael Jay, et al. “The Impact of General and Carbon-Related Environmental Knowledge on Attitudes and Behaviour of US Consumers.” Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 28, no. 3–4, Mar. 2012, pp. 238–263. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/0267257X.2012.659279. By Jessica Hayden

|

AuthorsConnor Bennet ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed