Political Science Club Officers

PRESIDENT Jackson Berridge

VICE PRESIDENT Dawson Gipp

SECRETARY Benjamin Brewer

TREASURER Elly Harder

If you have any questions or concerns about this newsletter,

please contact Dr. Ruth Alminas at (970) 247-6166 or by email at [email protected].

PRESIDENT Jackson Berridge

VICE PRESIDENT Dawson Gipp

SECRETARY Benjamin Brewer

TREASURER Elly Harder

If you have any questions or concerns about this newsletter,

please contact Dr. Ruth Alminas at (970) 247-6166 or by email at [email protected].

Nuclear Disarmament and a Political Science Career

By Elly Harder, Political Science Club Treasurer

Hello Fort Lewis students, faculty, & staff, and welcome to the Political Science Club’s April newsletter! I hope everyone's semester continues to be successful as we round the corner to the end of the term. In this newsletter we have a response article by Jackson Berridge making the case for nuclear disarmament & nonproliferation. It is a response to our last issue's article written by Benjamin Brewer, so if you haven't read that one go check it out here after reading this!

We also have a great student spotlight this time talking about my good friend and former roommate Tate Howes! He has been doing amazing work for international development in Bangladesh through the Covid-19 pandemic. So if you are interested in how he got involved in that and what his role looked like, make sure to check out that article by Dawson Gipp.

Finally if you are interested in partaking in a discussion on our two articles about what should be done with all these WMDs we have laying around, join us on Thursday, April 15th from 1-2 PM at the Noble Tent. We’d love to have as many brains in the room as can be allowed to provoke a good discussion, so keep up to date on the FLC app on our club page!

Enjoy the article and finish the semester strong!

We also have a great student spotlight this time talking about my good friend and former roommate Tate Howes! He has been doing amazing work for international development in Bangladesh through the Covid-19 pandemic. So if you are interested in how he got involved in that and what his role looked like, make sure to check out that article by Dawson Gipp.

Finally if you are interested in partaking in a discussion on our two articles about what should be done with all these WMDs we have laying around, join us on Thursday, April 15th from 1-2 PM at the Noble Tent. We’d love to have as many brains in the room as can be allowed to provoke a good discussion, so keep up to date on the FLC app on our club page!

Enjoy the article and finish the semester strong!

April Events

Meet Judge Nomoto Schumann!

Thursday, April 8, 1:00-2:00pm in Noble Outdoor Tent

Thinking about law school? Wondering what law school would be like? Want to know what life as an attorney is like? Want to know if you could be a judge? Join Judge Tam Nomoto Schumann to get answers to all your questions about the path to a career in the law. Sponsored by FLC Engage.

Nuclear Weapons: Effective Deterrent or Impending Doom?

Thursday, April 15, 1:00-2:00pm, Noble Outdoor Tent

Join the Political Science Club to continue the discussion about nuclear weapons! Do you see these weapons as a stabilizing influence in global politics as argued by PS Club Secretary Benjamin Brewer or as a threat to world peace along with our PS Club President Jackson Berridge? Come to listen, learn, and engage in a constructive dialogue about this important issue! Sponsored by Political Science Club.

Thursday, April 15, 1:00-2:00pm, Noble Outdoor Tent

Join the Political Science Club to continue the discussion about nuclear weapons! Do you see these weapons as a stabilizing influence in global politics as argued by PS Club Secretary Benjamin Brewer or as a threat to world peace along with our PS Club President Jackson Berridge? Come to listen, learn, and engage in a constructive dialogue about this important issue! Sponsored by Political Science Club.

Let’s Talk About It:

The Case for Nuclear Disarmament & Nonproliferation

By Jackson Berridge, Political Science Club President

belo I. Introduction

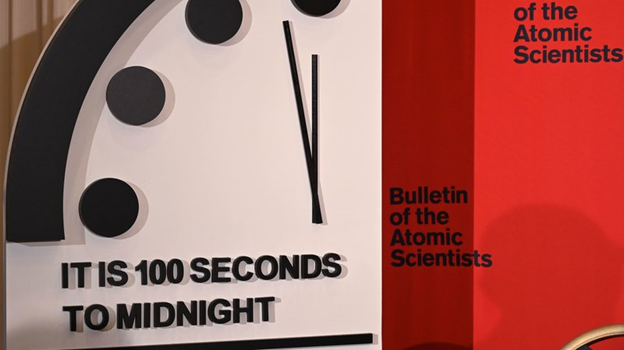

Humanity is less than two minutes away from annihilation. The above picture is the “Doomsday Clock” – a tool used by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, founded by Albert Einstein and the University of Chicago in 1945. The Clock was moved from 120 seconds to 100 seconds at the start of 2020 and kept at 100 seconds at the beginning of 2021. The Clock is a metaphor for how close the world is to an apocalypse (midnight) and uses the idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to indicate how close we are as a species to annihilation from threats to our planet. “The Doomsday Clock is set every year by the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board in consultation with its Board of Sponsors, which includes 13 Nobel laureates. The Clock has become a universally recognized indicator of the world’s vulnerability to catastrophe from nuclear weapons, climate change, and disruptive technologies in other domains” (Mecklin, “Doomsday Clock Statement”). 100 seconds is the closest humanity has ever come to midnight. For comparison, the clock was at 2 minutes to midnight during the Cold War. The persistent threat of nuclear destruction is at an all time high. The world is now in more political and civil turmoil than it has been in decades. At a time when technological and geopolitical threat multipliers are the norm, nuclear deterrence, or mutually assured destruction, is an outdated, unrealistically academic, and too unreliable a system for humanity to place our faith in. The only thing “assured” with MAD is our destruction.

II. The Unreliability of Mutually Assured Destruction

The Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) principle is a doctrine that came about during the Cold War between the US and Russia and justified the development of tens of thousands of nuclear weapons. Defined as a “principle of deterrence founded on the notion that a nuclear attack by one superpower would be met with an overwhelming nuclear counterattack such that both the attacker and the defender would be annihilated” (Britannica, “Mutual assured destruction”). If all that constitutes a superpower is being a state that possesses a nuclear weapon, then this doctrine would be relatively meaningful. However, three important factors make this doctrine unreliable. The first is that nuclear deterrence is not an indefinitely reliable strategy for avoiding nuclear annihilation, or even use (more on this in Section II).

The second is that being a superpower is about more than simply owning a nuclear weapon. Currently, nine countries have nuclear capability: the US, UK, Russia, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”). That list has the five UN Permanent Security Council Members (P5), and four others that many would be hard-pressed to consider a “superpower” from any dimension of analysis other than possessing nuclear weapons. While any one of these states may be dissuaded from attacking each other with a nuclear weapon for fear of mutual annihilation, there is no such direct security endangerment if they were to use a nuclear weapon on a non-nuclear-possessing state. The risk an attacking country faces in that circumstance is running afoul of a political alliance the defending state may have with another nuclear-possessing state, and even then, there is no guarantee of a nuclear retaliation. The international and domestic political consequences which the attacking country would face would indeed be severe, including harsh international economic sanctions, and perhaps even internationally justified militarized responses, but not necessarily a nuclear retaliation.

For example, in January 2020, when former President Trump ordered the bombing/ assassination of the high-ranking Iranian General Qasem Soleimani, and Iran responded by launching dozens of missiles on US-led military coalition bases (Wilkie, “Trump Responds to Iranian Attacks”), the world was momentarily concerned over Trump’s response. This is for good reason. There were many constraints on Trump’s response, but none of them the threat of a nuclear retaliation. This is because, had Trump responded with a nuclear attack, who would have “nuked” the US on Iran’s behalf? If MAD doctrine holds true, then Iran’s nuclear-possessing allies – China, India, and Russia - would have been dissuaded from attacking the US with a nuclear weapon for fear of mutual annihilation. None of them have a mutual defense pact with Iran, only military cooperation agreements. And who is to say that they would honor a mutual defense pact if it meant inviting nuclear destruction on themselves? If these nuclear-possessing states are rational actors, then any state without a nuclear weapon is unsafe. And if the solution to this dilemma is for every state to have nuclear capability, then the risk of any kind of regional conflict or accidental nuclear confrontation multiplies exponentially, forever (more on this in Section II).

The third major flaw with the MAD doctrine is a concept that was just mentioned: the rational actor model. Realism is the theory of International Relations (IR) that MAD is based in, and three of the fundamental assumptions of both are that 1) states are the only international actors that matter; 2) states are unitary actors (states speak and act with one voice and those of individual leaders and citizens/ private/ non-governmental or intergovernmental entities do not matter on the international stage; and 3) states are rational in the sense that rational decision-making leads to the pursuit of the national interest (meaning they are subject to a cost-benefit analysis) (McGlinchey, International Relations). The third assumption, that states are rational, is indeed true: a state exploring the possibility of using a nuclear weapon on another state will have to consider the costs and benefits of such actions. MAD is based on the assumption that if a state were to engage in this analysis when considering whether to use a nuclear weapon on another nuclear-possessing country, they would see that mutually assured destruction would be the inevitable outcome, and such a path would obviously be detrimental to the national interest.

The problem with this assumption is that it has to exist in a bubble to be valid, because states are not unitary actors, nor are they the only actors on the international stage. “States” are millions and billions of individuals, and a government, and individuals in their respective governments that may possess a different disposition than its population at any given moment in time. States are no longer the only actors of portent on the international stage. There are intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), such as the UN and NATO; there are militarized groups independent of their state of origin, such as ISIS/ ISIL and the Taliban; and there are other bodies such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and transnational corporations (TNCs), but they are of less relevance to the realist discussion. If an IGO such as NATO decided nuclear force was warranted and feasible, it would happen. If an independent military actor gets a hold of a nuclear weapon, then there are no theoretical safety-nets to protect any recipient of their ire from nuclear attack. If humans are focused on the long-term durability of our species, then we should not consider either of these possibilities to be implausible. Just because they have not happened yet does not mean that they never, ever, will; if there is any possibility in the future of a nuclear attack within our current system of mutually assured destruction, then we need to change that system today.

III. Why Disarmament and Nonproliferation?

The world may have only seen the use of two nuclear weapons on a civilian population so far, but there have been over 2,000 instances of nuclear bombs being detonated on earth since 1945 strictly for the purposes of testing or political showmanship (United Nations, “End Nuclear Testing”). Nuclear weapons tests are most often done underground, underwater, or in the atmosphere where the public cannot see them. The detonation of a nuclear weapon wreaks absolutely untold and unknown damage on our ecological systems and the health of individuals within a still-unknown radius of these explosions (Prăvălie, “Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences”). To address the widespread and destructive nature of these tests, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) was introduced to the international community. The treaty has yet to enter in to force, as it is still pending the signatures of 8 countries who were part of the original 44 with nuclear capability at the time the treaty was introduced who are required to sign and ratify it before it can be entered into force, including signatures from China, India, Israel, Pakistan, North Korea, and the US. However, due largely to this treaty regime, nuclear testing has reduced to almost zero in recent decades. The last time the US tested a nuclear weapon was in 1992, Russia’s last test was in 1990, the UK’s in 1991, France and Chinas’ in 1996, and North Korea’s in 2017 (United Nations, “End Nuclear Testing”). The success of this treaty, despite it never even having been entered into force and made legally-binding, should not be viewed as justification to maintain the status-quo, but as a signal for the success that comprehensive monitoring and enforcement treaty regimes for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation can attain.

Mutually assured destruction is not the reason we have seen a reduction in great-power wars and international wars in general, nor is it the reason we have seen a reduction in the humanitarian costs of war, and it is especially not the reason we can expect to see little to no international wars between superpowers in the future. See Goldstein (2015) for discussion on the empirical reduction of world-wide violence. Gartzke (2007) attributes the reduction of international wars and “militarized interstate disputes” (MIDs) since World War II to economic interdependence through liberalized interstate trade, the development of mutual interests through globalization, and the rise in domestic economic development. The same analysis concluded that “nuclear weapons status show[ed] no significant effect on dispute behavior” between states since WWII. The Cuban missile crisis at the height of the Cold War directly and exclusively resulted from the presence of nuclear weapons in the situation. There was no other cause for concern that would have constituted a “crisis,” and the proliferation of nuclear weapons was nearly responsible for their very own use. The advent of robust intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) such as the United Nations and the European Union since the end of WWII provide dispute-resolution procedures and bodies that, coupled with the ease by which resources and security are obtained through trade and diplomacy through these IGOs, far reduce what can be gained by war as opposed to what can be gained by not going to war. Conflicts have gotten less deadly not because someone has a nuclear weapon somewhere else, but because the technology and methods that conflicts are fought with are far more sophisticated now than they have ever been. Additionally, public opinion toward war has influenced international policy to the point that a state killing people in mass is no longer acceptable under almost any circumstance.

While nuclear testing has all but ceased, and violence from conflict has diminished exponentially, there are still major causes for concern. There have been 32 instances of nuclear weapons accidents, known as “broken arrows,” since 1950 (Atomic Archive, “Broken Arrows”). The term “broken arrow” is used for any “unexpected event involving nuclear weapons that result in the accidental launching, firing, detonating, theft or loss of the weapon (Atomic Archive)." Since 1950, there have been six nuclear weapons lost that have never been recovered (Atomic Archive). That should be one of the most bone-chilling things that anyone could ever read. Six nuclear weapons that have been reported missing and have never been found. Broken arrows have included accidental explosions through technical failure in the vessels carrying them (many near populated areas), and have resulted in the spread of tens of thousands of pounds of irrecoverable radioactive material and the loss of dozens of lives (Atomic Archive).

Beyond accidents which can not be accounted for, here have been 25 “close calls” that the US has made the public aware of where we were on the brink of a nuclear war due to misinformation (Future of Life, “Close Calls”). See the Future of Life’s interactive timeline below for the details of each one (that we know of).

Humanity is less than two minutes away from annihilation. The above picture is the “Doomsday Clock” – a tool used by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, founded by Albert Einstein and the University of Chicago in 1945. The Clock was moved from 120 seconds to 100 seconds at the start of 2020 and kept at 100 seconds at the beginning of 2021. The Clock is a metaphor for how close the world is to an apocalypse (midnight) and uses the idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to indicate how close we are as a species to annihilation from threats to our planet. “The Doomsday Clock is set every year by the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board in consultation with its Board of Sponsors, which includes 13 Nobel laureates. The Clock has become a universally recognized indicator of the world’s vulnerability to catastrophe from nuclear weapons, climate change, and disruptive technologies in other domains” (Mecklin, “Doomsday Clock Statement”). 100 seconds is the closest humanity has ever come to midnight. For comparison, the clock was at 2 minutes to midnight during the Cold War. The persistent threat of nuclear destruction is at an all time high. The world is now in more political and civil turmoil than it has been in decades. At a time when technological and geopolitical threat multipliers are the norm, nuclear deterrence, or mutually assured destruction, is an outdated, unrealistically academic, and too unreliable a system for humanity to place our faith in. The only thing “assured” with MAD is our destruction.

II. The Unreliability of Mutually Assured Destruction

The Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) principle is a doctrine that came about during the Cold War between the US and Russia and justified the development of tens of thousands of nuclear weapons. Defined as a “principle of deterrence founded on the notion that a nuclear attack by one superpower would be met with an overwhelming nuclear counterattack such that both the attacker and the defender would be annihilated” (Britannica, “Mutual assured destruction”). If all that constitutes a superpower is being a state that possesses a nuclear weapon, then this doctrine would be relatively meaningful. However, three important factors make this doctrine unreliable. The first is that nuclear deterrence is not an indefinitely reliable strategy for avoiding nuclear annihilation, or even use (more on this in Section II).

The second is that being a superpower is about more than simply owning a nuclear weapon. Currently, nine countries have nuclear capability: the US, UK, Russia, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”). That list has the five UN Permanent Security Council Members (P5), and four others that many would be hard-pressed to consider a “superpower” from any dimension of analysis other than possessing nuclear weapons. While any one of these states may be dissuaded from attacking each other with a nuclear weapon for fear of mutual annihilation, there is no such direct security endangerment if they were to use a nuclear weapon on a non-nuclear-possessing state. The risk an attacking country faces in that circumstance is running afoul of a political alliance the defending state may have with another nuclear-possessing state, and even then, there is no guarantee of a nuclear retaliation. The international and domestic political consequences which the attacking country would face would indeed be severe, including harsh international economic sanctions, and perhaps even internationally justified militarized responses, but not necessarily a nuclear retaliation.

For example, in January 2020, when former President Trump ordered the bombing/ assassination of the high-ranking Iranian General Qasem Soleimani, and Iran responded by launching dozens of missiles on US-led military coalition bases (Wilkie, “Trump Responds to Iranian Attacks”), the world was momentarily concerned over Trump’s response. This is for good reason. There were many constraints on Trump’s response, but none of them the threat of a nuclear retaliation. This is because, had Trump responded with a nuclear attack, who would have “nuked” the US on Iran’s behalf? If MAD doctrine holds true, then Iran’s nuclear-possessing allies – China, India, and Russia - would have been dissuaded from attacking the US with a nuclear weapon for fear of mutual annihilation. None of them have a mutual defense pact with Iran, only military cooperation agreements. And who is to say that they would honor a mutual defense pact if it meant inviting nuclear destruction on themselves? If these nuclear-possessing states are rational actors, then any state without a nuclear weapon is unsafe. And if the solution to this dilemma is for every state to have nuclear capability, then the risk of any kind of regional conflict or accidental nuclear confrontation multiplies exponentially, forever (more on this in Section II).

The third major flaw with the MAD doctrine is a concept that was just mentioned: the rational actor model. Realism is the theory of International Relations (IR) that MAD is based in, and three of the fundamental assumptions of both are that 1) states are the only international actors that matter; 2) states are unitary actors (states speak and act with one voice and those of individual leaders and citizens/ private/ non-governmental or intergovernmental entities do not matter on the international stage; and 3) states are rational in the sense that rational decision-making leads to the pursuit of the national interest (meaning they are subject to a cost-benefit analysis) (McGlinchey, International Relations). The third assumption, that states are rational, is indeed true: a state exploring the possibility of using a nuclear weapon on another state will have to consider the costs and benefits of such actions. MAD is based on the assumption that if a state were to engage in this analysis when considering whether to use a nuclear weapon on another nuclear-possessing country, they would see that mutually assured destruction would be the inevitable outcome, and such a path would obviously be detrimental to the national interest.

The problem with this assumption is that it has to exist in a bubble to be valid, because states are not unitary actors, nor are they the only actors on the international stage. “States” are millions and billions of individuals, and a government, and individuals in their respective governments that may possess a different disposition than its population at any given moment in time. States are no longer the only actors of portent on the international stage. There are intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), such as the UN and NATO; there are militarized groups independent of their state of origin, such as ISIS/ ISIL and the Taliban; and there are other bodies such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and transnational corporations (TNCs), but they are of less relevance to the realist discussion. If an IGO such as NATO decided nuclear force was warranted and feasible, it would happen. If an independent military actor gets a hold of a nuclear weapon, then there are no theoretical safety-nets to protect any recipient of their ire from nuclear attack. If humans are focused on the long-term durability of our species, then we should not consider either of these possibilities to be implausible. Just because they have not happened yet does not mean that they never, ever, will; if there is any possibility in the future of a nuclear attack within our current system of mutually assured destruction, then we need to change that system today.

III. Why Disarmament and Nonproliferation?

The world may have only seen the use of two nuclear weapons on a civilian population so far, but there have been over 2,000 instances of nuclear bombs being detonated on earth since 1945 strictly for the purposes of testing or political showmanship (United Nations, “End Nuclear Testing”). Nuclear weapons tests are most often done underground, underwater, or in the atmosphere where the public cannot see them. The detonation of a nuclear weapon wreaks absolutely untold and unknown damage on our ecological systems and the health of individuals within a still-unknown radius of these explosions (Prăvălie, “Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences”). To address the widespread and destructive nature of these tests, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) was introduced to the international community. The treaty has yet to enter in to force, as it is still pending the signatures of 8 countries who were part of the original 44 with nuclear capability at the time the treaty was introduced who are required to sign and ratify it before it can be entered into force, including signatures from China, India, Israel, Pakistan, North Korea, and the US. However, due largely to this treaty regime, nuclear testing has reduced to almost zero in recent decades. The last time the US tested a nuclear weapon was in 1992, Russia’s last test was in 1990, the UK’s in 1991, France and Chinas’ in 1996, and North Korea’s in 2017 (United Nations, “End Nuclear Testing”). The success of this treaty, despite it never even having been entered into force and made legally-binding, should not be viewed as justification to maintain the status-quo, but as a signal for the success that comprehensive monitoring and enforcement treaty regimes for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation can attain.

Mutually assured destruction is not the reason we have seen a reduction in great-power wars and international wars in general, nor is it the reason we have seen a reduction in the humanitarian costs of war, and it is especially not the reason we can expect to see little to no international wars between superpowers in the future. See Goldstein (2015) for discussion on the empirical reduction of world-wide violence. Gartzke (2007) attributes the reduction of international wars and “militarized interstate disputes” (MIDs) since World War II to economic interdependence through liberalized interstate trade, the development of mutual interests through globalization, and the rise in domestic economic development. The same analysis concluded that “nuclear weapons status show[ed] no significant effect on dispute behavior” between states since WWII. The Cuban missile crisis at the height of the Cold War directly and exclusively resulted from the presence of nuclear weapons in the situation. There was no other cause for concern that would have constituted a “crisis,” and the proliferation of nuclear weapons was nearly responsible for their very own use. The advent of robust intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) such as the United Nations and the European Union since the end of WWII provide dispute-resolution procedures and bodies that, coupled with the ease by which resources and security are obtained through trade and diplomacy through these IGOs, far reduce what can be gained by war as opposed to what can be gained by not going to war. Conflicts have gotten less deadly not because someone has a nuclear weapon somewhere else, but because the technology and methods that conflicts are fought with are far more sophisticated now than they have ever been. Additionally, public opinion toward war has influenced international policy to the point that a state killing people in mass is no longer acceptable under almost any circumstance.

While nuclear testing has all but ceased, and violence from conflict has diminished exponentially, there are still major causes for concern. There have been 32 instances of nuclear weapons accidents, known as “broken arrows,” since 1950 (Atomic Archive, “Broken Arrows”). The term “broken arrow” is used for any “unexpected event involving nuclear weapons that result in the accidental launching, firing, detonating, theft or loss of the weapon (Atomic Archive)." Since 1950, there have been six nuclear weapons lost that have never been recovered (Atomic Archive). That should be one of the most bone-chilling things that anyone could ever read. Six nuclear weapons that have been reported missing and have never been found. Broken arrows have included accidental explosions through technical failure in the vessels carrying them (many near populated areas), and have resulted in the spread of tens of thousands of pounds of irrecoverable radioactive material and the loss of dozens of lives (Atomic Archive).

Beyond accidents which can not be accounted for, here have been 25 “close calls” that the US has made the public aware of where we were on the brink of a nuclear war due to misinformation (Future of Life, “Close Calls”). See the Future of Life’s interactive timeline below for the details of each one (that we know of).

Anything can happen, and amid a fog of war, anything that is perceived as a nuclear threat may be responded to with nuclear force immediately. Such is the nature of hair-trigger policies and the employment of second-strike capability. Dr. William J. Perry, former US Secretary of Defense and former Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering under Bill Clinton, Stanford professor, and mathematician, had his career during and immediately after the Cold War. He has personally experienced two “false alarms''' in US command – situations that nearly caused a nuclear attack on our part. In one situation, a training tape was put into the monitoring computer instead of the real one, and the officer on duty saw 200 Nuclear Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) incoming from the Soviet Union at 3:00 in the morning. Perry had this to say about the event to NPR in an interview:

“Fortunately, that night the watch officer was a very intelligent and a very responsible person. He dug deeply. And instead of calling the president in the middle of the night, waking him up and giving him five to 10 minutes to make a decision to launch, he dug into it and concluded it was an error. I know about that because he called me in the middle of the night to tell me about it. So I'll never forget that night.” (Perry, “False Missile Warnings”)

“I’ll never forget that night” – the night we could have started World War III because someone put the wrong tape in the machine. Perry said that the Soviet Union had a comparable situation where the watch officer disobeyed orders to call the president and request to fire nuclear weapons on the US because he thought the monitoring equipment was malfunctioning. He was right. That man’s deeds were made into a movie called “The Man Who Saved the World.” According to Perry, the way our nuclear response (the single idea which the success of mutually assured destruction is predicated on) works, is that:

“One person makes the decision - the watch officer. That decision then - if there's time, there will be a conference of other people to give other judgments on it. But if there's not time, then it might go directly to the president. And then the president if he's woken in bed in the middle of the night, might have five to 10 minutes to decide whether he should launch our missiles in response to that. And if he launches them and if he then discovers a mistake, there's nothing he can do to recall them. There's nothing he can do to abort them in flight. He has mistakenly started World War III.” (Perry).

These examples may be anecdotes. The examples from the interactive chart of nuclear “close calls” may be anecdotal. But if we are considering letting mutually assured destruction endure as a policy into the indefinite future, then any one anecdote could turn into World War III. With the current global stockpile of 13,500 ready-to-go nuclear warheads (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”), are we willing to risk that the next “broken arrow” or “close call” does not result in the next World War? Or in the very extinction of life as we know it? To put it another way, and to quote a data scientist named Martin Hellman, who has been focused on determining the risk of nuclear war for several decades: “Can we responsibly bet humanity’s existence on a strategy for which the risk of failure is totally unknown (Hellman & Cerf, “An existential discussion”)?"

IV. What Can We Do?

100 seconds to midnight is a grim evaluation of our current prospects, but it is probably accurate. Glimmers of hope exist though. In 1986 there were approximately 70,300 nuclear warheads stockpiled across 44 different countries with nuclear capability (United Nations, “Ending Nuclear Testing”). Today it is only approximately 13,500 across only 9 countries, and 4,000 of those are awaiting dismantlement (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”). That is still enough to destroy the world hundreds of times over, but it is an 80% decline (Nuclear Threat Initiative, “The Nuclear Threat”). This reduction is due to the efforts on the part of governments and citizens engaged in bringing about global zero – the complete disarmament and nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. Because of these efforts, 25 treaties mandating nuclear disarmament, the cessation of further development and testing, and establishing comprehensive and effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms (both political and technological) have been created (Atomic Archive, “Arms Control Treaties”).

The Biden Administration has offered to extend the New START arms control agreement with Russia for five years, a treaty which the previous Trump Administration was not going to extend, and aims to limit the number of deployed nuclear weapons of both the US and Russia to 1,500 – down from the current 2200 (Mecklin, “Doomsday Clock Statement”). The US and Russia hold 90% of the world’s current nuclear stockpile (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”), making the New START treaty one of the most important agreements we have in the entire world. The new administration also expressed a desire to re-enter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) treaty, colloquially known as the “Iran Deal,” which the previous administration left in 2018 (Davenport & Reif). Leaving the JCPOA resulted in the US losing all enforcement and monitoring capability in the region: “The U.S. has surrendered the victories of intrusive nuclear controls (Lopez, “A day that will live on in acrimony”)."

Reentering the JCPOA gives the US a chance to mend diplomatic relations with Iran along one of the most important dimensions, that of our nuclear relationship. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, or the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty have been the two strongest multilateral disarmament treaties thus far. The NPT has been ratified by 191 countries, making it the most widely adhered to arms limitation and disarmament agreement, was voted by all nuclear states to be extended indefinitely in 1995, and mandates that all Parties to the Treaty “undertake effective measures in the direction of nuclear disarmament” (United Nations, “(NPT)”). Since the ratification of this treaty and the CTBT mentioned above which limits the testing and development of nuclear weapons, 35 countries have gotten rid of their nuclear stockpile and nuclear weapons-manufacturing programs.

Through a five-phase plan, a global collective called Global Zero has introduced a strategy to reach, well, global zero, through “a treaty among the world’s nine nuclear-armed nations that will remove all nuclear weapons from service by 2030 and ensure they are permanently dismantled by 2045 (Global Zero, “Reaching Zero”)." There are dozens of other NGOs with the directive of bringing about global zero who are always looking for participation and support. These NGOs, citizens, and governments working towards Global Zero represent meaningful hope for living in a world free of nuclear weapons. We are not out of the weeds yet though – we still need to make it there without causing World War III. Anyone can help, because nuclear proliferation was not inevitable, it was the cause of individuals who believed it was the most secure path for humanity. Individuals make the difference when they decide to disobey orders to launch nukes off a hunch. Individuals like you and me can make the difference simply by engaging in conversations about nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation, because waiting until the day the bombs drop is a hopelessly perilous mindset that we do not have to accept. It is individuals like us who will be responsible for our future – hopefully a future that is free from the threat of nuclear weapons.

“Fortunately, that night the watch officer was a very intelligent and a very responsible person. He dug deeply. And instead of calling the president in the middle of the night, waking him up and giving him five to 10 minutes to make a decision to launch, he dug into it and concluded it was an error. I know about that because he called me in the middle of the night to tell me about it. So I'll never forget that night.” (Perry, “False Missile Warnings”)

“I’ll never forget that night” – the night we could have started World War III because someone put the wrong tape in the machine. Perry said that the Soviet Union had a comparable situation where the watch officer disobeyed orders to call the president and request to fire nuclear weapons on the US because he thought the monitoring equipment was malfunctioning. He was right. That man’s deeds were made into a movie called “The Man Who Saved the World.” According to Perry, the way our nuclear response (the single idea which the success of mutually assured destruction is predicated on) works, is that:

“One person makes the decision - the watch officer. That decision then - if there's time, there will be a conference of other people to give other judgments on it. But if there's not time, then it might go directly to the president. And then the president if he's woken in bed in the middle of the night, might have five to 10 minutes to decide whether he should launch our missiles in response to that. And if he launches them and if he then discovers a mistake, there's nothing he can do to recall them. There's nothing he can do to abort them in flight. He has mistakenly started World War III.” (Perry).

These examples may be anecdotes. The examples from the interactive chart of nuclear “close calls” may be anecdotal. But if we are considering letting mutually assured destruction endure as a policy into the indefinite future, then any one anecdote could turn into World War III. With the current global stockpile of 13,500 ready-to-go nuclear warheads (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”), are we willing to risk that the next “broken arrow” or “close call” does not result in the next World War? Or in the very extinction of life as we know it? To put it another way, and to quote a data scientist named Martin Hellman, who has been focused on determining the risk of nuclear war for several decades: “Can we responsibly bet humanity’s existence on a strategy for which the risk of failure is totally unknown (Hellman & Cerf, “An existential discussion”)?"

IV. What Can We Do?

100 seconds to midnight is a grim evaluation of our current prospects, but it is probably accurate. Glimmers of hope exist though. In 1986 there were approximately 70,300 nuclear warheads stockpiled across 44 different countries with nuclear capability (United Nations, “Ending Nuclear Testing”). Today it is only approximately 13,500 across only 9 countries, and 4,000 of those are awaiting dismantlement (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”). That is still enough to destroy the world hundreds of times over, but it is an 80% decline (Nuclear Threat Initiative, “The Nuclear Threat”). This reduction is due to the efforts on the part of governments and citizens engaged in bringing about global zero – the complete disarmament and nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. Because of these efforts, 25 treaties mandating nuclear disarmament, the cessation of further development and testing, and establishing comprehensive and effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms (both political and technological) have been created (Atomic Archive, “Arms Control Treaties”).

The Biden Administration has offered to extend the New START arms control agreement with Russia for five years, a treaty which the previous Trump Administration was not going to extend, and aims to limit the number of deployed nuclear weapons of both the US and Russia to 1,500 – down from the current 2200 (Mecklin, “Doomsday Clock Statement”). The US and Russia hold 90% of the world’s current nuclear stockpile (Davenport & Reif, “Who Has What?”), making the New START treaty one of the most important agreements we have in the entire world. The new administration also expressed a desire to re-enter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) treaty, colloquially known as the “Iran Deal,” which the previous administration left in 2018 (Davenport & Reif). Leaving the JCPOA resulted in the US losing all enforcement and monitoring capability in the region: “The U.S. has surrendered the victories of intrusive nuclear controls (Lopez, “A day that will live on in acrimony”)."

Reentering the JCPOA gives the US a chance to mend diplomatic relations with Iran along one of the most important dimensions, that of our nuclear relationship. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, or the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty have been the two strongest multilateral disarmament treaties thus far. The NPT has been ratified by 191 countries, making it the most widely adhered to arms limitation and disarmament agreement, was voted by all nuclear states to be extended indefinitely in 1995, and mandates that all Parties to the Treaty “undertake effective measures in the direction of nuclear disarmament” (United Nations, “(NPT)”). Since the ratification of this treaty and the CTBT mentioned above which limits the testing and development of nuclear weapons, 35 countries have gotten rid of their nuclear stockpile and nuclear weapons-manufacturing programs.

Through a five-phase plan, a global collective called Global Zero has introduced a strategy to reach, well, global zero, through “a treaty among the world’s nine nuclear-armed nations that will remove all nuclear weapons from service by 2030 and ensure they are permanently dismantled by 2045 (Global Zero, “Reaching Zero”)." There are dozens of other NGOs with the directive of bringing about global zero who are always looking for participation and support. These NGOs, citizens, and governments working towards Global Zero represent meaningful hope for living in a world free of nuclear weapons. We are not out of the weeds yet though – we still need to make it there without causing World War III. Anyone can help, because nuclear proliferation was not inevitable, it was the cause of individuals who believed it was the most secure path for humanity. Individuals make the difference when they decide to disobey orders to launch nukes off a hunch. Individuals like you and me can make the difference simply by engaging in conversations about nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation, because waiting until the day the bombs drop is a hopelessly perilous mindset that we do not have to accept. It is individuals like us who will be responsible for our future – hopefully a future that is free from the threat of nuclear weapons.

Works Cited

Atomic Archive, “Arms Control Treaties.” Atomicarchive.com, 2020, https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/treaties/index.html.

Atomic Archive, “Broken Arrows: Nuclear Weapons Accidents.” Atomicarchive.com, 2020, https://www.atomicarchive.com/almanac/broken-arrows/index.html.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Mutual assured destruction." Encyclopedia Britannica, July 17, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mutual-assured-destruction.

Davenport, Kelsey & Reif, Kingston, “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association, August 2020, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat.

Future of Life Institute, “Accidental Nuclear War: A Timeline of Close Calls.” Futureoflife.org, 2019, https://futureoflife.org/background/nuclear-close-calls-a-timeline/.

Gartzke, Erik. “The Capitalist Peace.” American Journal of Political Science 51, no. 1, 2007, 166–91, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00244.x.

Global Zero, “Reaching Zero.” Globalzero.org, 2021, https://www.globalzero.org/reaching-zero/.

Goldstein, Joshua. “Think Again: War.” Foreignpolicy.com, August 15, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/08/15/think-again-war/.

Hellman, Martin E. & Cerf, Vinton G., “An existential discussion: What is the probability of nuclear war?” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, March 18, 2021, https://hebulletin.org/2021/03/an-existential-discussion-what-is-the-probability-of-nuclear-war/.

Lopez, George A., “May 8, 2018: A day that will live on in acrimony.” Responsible Statecraft, May 8, 2020, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2020/05/08/may-8-2018-a-day-that-will-live-in-acrimony/.

McGlinchey, Stephen, ed. International Relations. Bristol, England, E-International Relations, 2017. https://www.e-ir.info/publication/beginners-textbook-international-relations/.

Mecklin, John, “2021 Doomsday Clock Statement.” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, January 27, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/.

Nuclear Threat Initiative, “The Nuclear Threat.” December 31, 2015, https://www.nti.org/learn/nuclear/.

Perry, William J, “Ex-Defense Chief William Perry on False Missile Warnings.” NPR, January 16, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/01/16/578247161/ex-defense-chief-william-perry-on-false-missile-warnings.

Prăvălie, Remus, “Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences: A Global Perspective.” Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences,2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4165831/#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20large%20number%20of,socially%20destroyed%20sites%2C%20due%20to.

United Nations, “Ending Nuclear Testing.” United Nations, 2020, https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-nuclear-tests-day/history.

Wilkie, Christina, “Trump responds to Iranian attacks: ‘All is well!’” CNBC, January 7, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/07/trump-responds-to-iranian-attacks-on-us-forces.html.

United Nations, “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT): Text of the Treaty.” Un.org, 1968, https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text.

Atomic Archive, “Arms Control Treaties.” Atomicarchive.com, 2020, https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/treaties/index.html.

Atomic Archive, “Broken Arrows: Nuclear Weapons Accidents.” Atomicarchive.com, 2020, https://www.atomicarchive.com/almanac/broken-arrows/index.html.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Mutual assured destruction." Encyclopedia Britannica, July 17, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mutual-assured-destruction.

Davenport, Kelsey & Reif, Kingston, “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance.” Arms Control Association, August 2020, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat.

Future of Life Institute, “Accidental Nuclear War: A Timeline of Close Calls.” Futureoflife.org, 2019, https://futureoflife.org/background/nuclear-close-calls-a-timeline/.

Gartzke, Erik. “The Capitalist Peace.” American Journal of Political Science 51, no. 1, 2007, 166–91, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00244.x.

Global Zero, “Reaching Zero.” Globalzero.org, 2021, https://www.globalzero.org/reaching-zero/.

Goldstein, Joshua. “Think Again: War.” Foreignpolicy.com, August 15, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/08/15/think-again-war/.

Hellman, Martin E. & Cerf, Vinton G., “An existential discussion: What is the probability of nuclear war?” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, March 18, 2021, https://hebulletin.org/2021/03/an-existential-discussion-what-is-the-probability-of-nuclear-war/.

Lopez, George A., “May 8, 2018: A day that will live on in acrimony.” Responsible Statecraft, May 8, 2020, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2020/05/08/may-8-2018-a-day-that-will-live-in-acrimony/.

McGlinchey, Stephen, ed. International Relations. Bristol, England, E-International Relations, 2017. https://www.e-ir.info/publication/beginners-textbook-international-relations/.

Mecklin, John, “2021 Doomsday Clock Statement.” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, January 27, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/.

Nuclear Threat Initiative, “The Nuclear Threat.” December 31, 2015, https://www.nti.org/learn/nuclear/.

Perry, William J, “Ex-Defense Chief William Perry on False Missile Warnings.” NPR, January 16, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/01/16/578247161/ex-defense-chief-william-perry-on-false-missile-warnings.

Prăvălie, Remus, “Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences: A Global Perspective.” Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences,2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4165831/#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20large%20number%20of,socially%20destroyed%20sites%2C%20due%20to.

United Nations, “Ending Nuclear Testing.” United Nations, 2020, https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-nuclear-tests-day/history.

Wilkie, Christina, “Trump responds to Iranian attacks: ‘All is well!’” CNBC, January 7, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/07/trump-responds-to-iranian-attacks-on-us-forces.html.

United Nations, “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT): Text of the Treaty.” Un.org, 1968, https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text.

Let's Continue the Discussion!

This semester, the Political Science Club would like to invite the FLC community to participate in a series of discussions about hot-button issues in the classroom and beyond. Our goal is to practice creating safe environments for constructive dialogue across a wide variety of differing perspectives. Above all, we ask that as you join us in this conversation, you do not try to “win” the conversation. This is not a competition. We are all here to listen and learn. To make sure we can create the conditions for constructive dialogue, we ask that you please read and comply with the following ground rules.

Ground Rules for Discussion

The Political Science Club and all of our events are open to any FLC students who are interested in political engagement and civil discourse. If you cannot not abide by these ground rules, we will ask you to remove yourself from the conversation until you can.

- Be authentic and honest.

- Listen (or read) carefully, especially if you disagree. Do not formulate a response until you have first taken the time to understand what is being communicated.

- Ask questions to help you understand perspectives different from your own.

- Be respectful when asking for evidence supporting a statement that has been made.

- Don’t assume anything about one another’s beliefs, ideas or identities.

- Don’t make generalizations about any group of people. Don’t use the words ‘always’ or ‘never’.

- Recognize the difference between facts and opinions. Both are legitimate when expressed appropriately, but we need to be careful not to confuse the two.

- Keep an open mind and remember that we are here to learn from each other and solve shared problems rather than to convince or win arguments.

- Be patient with one another and ourselves in cases of low knowledge or awareness, remembering that our intention is to learn from each other.

- Acknowledge intent and address impact. Assume that others are speaking and acting from a place of good intent. At the same time, if our actions negatively impact others, we must address, understand, and take responsibility for that impact.

- Practice inclusivity and appreciate diversity of the identities, perspectives, and experiences in our community.

The discussion for this topic will be held on April 15th in the Noble Tent outdoor learning space during college hour from 1:00 - 2:00 PM. Be there!

Introducing FLC Engage

By Sydney Halford, Campus Outreach and Events Coordinator for FLC Engage

Hi Skyhawks! My name is Sydney Halford and I am the Campus Outreach and Events Coordinator for the Fort Lewis College Engagement Collaborative, also known as FLC Engage.

What is FLC Engage? Well, the Fort Lewis College Engagement Collaborative, is a group of FLC students, faculty, and staff who share a mission to engage Skyhawks in social issues and civic affairs most important to them. We aim to connect the student body of Fort Lewis College to the political conversation in a new and fun way. Our hope is to accomplish this through a collaboration of education and community engagement. We believe that it is important to get the campus community engaged to ensure students become well-informed participants in the American democratic process so they may have a greater impact on civil affairs.

My job for FLC Engage is to act as a liaison between our organization and our campus community. We hope to collaborate with the diverse and hard-working groups we have on campus to push our message and to ensure that everyone gets engaged. Civil engagement is not just voting, it’s finding different ways to support and advocate for the ideas that you care about! If you would like to know more about what we do or get involved feel free to contact me at [email protected]. We can’t wait to work with you!

What is FLC Engage? Well, the Fort Lewis College Engagement Collaborative, is a group of FLC students, faculty, and staff who share a mission to engage Skyhawks in social issues and civic affairs most important to them. We aim to connect the student body of Fort Lewis College to the political conversation in a new and fun way. Our hope is to accomplish this through a collaboration of education and community engagement. We believe that it is important to get the campus community engaged to ensure students become well-informed participants in the American democratic process so they may have a greater impact on civil affairs.

My job for FLC Engage is to act as a liaison between our organization and our campus community. We hope to collaborate with the diverse and hard-working groups we have on campus to push our message and to ensure that everyone gets engaged. Civil engagement is not just voting, it’s finding different ways to support and advocate for the ideas that you care about! If you would like to know more about what we do or get involved feel free to contact me at [email protected]. We can’t wait to work with you!

FLC Alumni Spotlight on Tate Howes

By Dawson Gipp, Political Science Club Vice President

In this brave new world we face, what does this future for us students, soon to be professionals, look like? Has this new reality of remote learning, virtual meetings, and an overall more home based work environment changed the way our careers will function compared to previous generations? Or will our careers return to a normal work environment with minor changes? As we try to gain some perspective in this uncharted territory, I’ve reached out to an FLC alum and former Political Science Club Vice President, Tate Howes, who has recently dealt first hand with how this pandemic may affect our future careers.

Tate, who graduated in 2020 as a double major in Anthropology and Political Science, had been interested in international development since high school, but had written off his current field as an unfeasible pipe dream. It was only after pursuing his interests here at the Fort that he found that international development was in fact a legitimate career path, stating that “once that became a concrete objective there was nothing else”. So, in the summer of 2019, he received an internship on a food security project with an international NGO (nongovernmental organization), based in Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Only to find out that, “it looks nothing like what I expected it to, but it was a much more effective version of the very ill-informed notion I had of it in high school”. As Tate got this real world experience with what this sort of project implementation looks like in the field, he was learning what his role in that might be. As he puts it “my role is less focused on implementation at the field level, and is more about facilitating organizational capacity to enable locals to develop their communities in a manner that will be sustainable following a projects conclusion.” Although it wasn’t quite the work that he had expected to do, he said the way he sees it is, “If you love the mission, you love the work”. Which ended up leading him to some other opportunities, during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020.

So, it’s a year later and Tate, having just recently graduated, at first spent the early part of the summer of 2020, like most of us, watching Tiger King. However, he knew he could do something more productive with his time and decided to contact his old boss to see if there was anything he could do to help. Getting taken on for another 4 months, he was doing everything remotely this time, “which was interesting logistically”, he said, “because he was based in Colorado, answering to someone else based in New York, someone in Maine, and a team in Bangladesh. So the time zones were a nightmare! But that was really beneficial for learning how you can be effective under unusual circumstances, and just to give back during Covid when there is so much going on in the world”. I asked Tate if he considered continuing that kind of work, only to find out that he was given a permanent job with that same company. Providing remote support out of Colorado for the project in Bangladesh, right from his bedroom.

Tate, preferring to work in Bangladesh, does for the moment have to face this change in the world. However, this change is offering him other opportunities as well. He is also currently working on his Masters degree in Global Technology and Development. He’s essentially studying the role that technology plays in facilitating global development, remotely of course. So if we can take away anything from his experience, it’s plain to see. Some of our careers may be much different than what we expected, which might be more beneficial than we thought or it may remove that special factor on why we sought it in the first place, at least for the moment.

Tate, who graduated in 2020 as a double major in Anthropology and Political Science, had been interested in international development since high school, but had written off his current field as an unfeasible pipe dream. It was only after pursuing his interests here at the Fort that he found that international development was in fact a legitimate career path, stating that “once that became a concrete objective there was nothing else”. So, in the summer of 2019, he received an internship on a food security project with an international NGO (nongovernmental organization), based in Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Only to find out that, “it looks nothing like what I expected it to, but it was a much more effective version of the very ill-informed notion I had of it in high school”. As Tate got this real world experience with what this sort of project implementation looks like in the field, he was learning what his role in that might be. As he puts it “my role is less focused on implementation at the field level, and is more about facilitating organizational capacity to enable locals to develop their communities in a manner that will be sustainable following a projects conclusion.” Although it wasn’t quite the work that he had expected to do, he said the way he sees it is, “If you love the mission, you love the work”. Which ended up leading him to some other opportunities, during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020.

So, it’s a year later and Tate, having just recently graduated, at first spent the early part of the summer of 2020, like most of us, watching Tiger King. However, he knew he could do something more productive with his time and decided to contact his old boss to see if there was anything he could do to help. Getting taken on for another 4 months, he was doing everything remotely this time, “which was interesting logistically”, he said, “because he was based in Colorado, answering to someone else based in New York, someone in Maine, and a team in Bangladesh. So the time zones were a nightmare! But that was really beneficial for learning how you can be effective under unusual circumstances, and just to give back during Covid when there is so much going on in the world”. I asked Tate if he considered continuing that kind of work, only to find out that he was given a permanent job with that same company. Providing remote support out of Colorado for the project in Bangladesh, right from his bedroom.

Tate, preferring to work in Bangladesh, does for the moment have to face this change in the world. However, this change is offering him other opportunities as well. He is also currently working on his Masters degree in Global Technology and Development. He’s essentially studying the role that technology plays in facilitating global development, remotely of course. So if we can take away anything from his experience, it’s plain to see. Some of our careers may be much different than what we expected, which might be more beneficial than we thought or it may remove that special factor on why we sought it in the first place, at least for the moment.

Why is Political Engagement Important to You?

“Political engagement to me means that I have a space and a voice in my community and in my government to advocate for causes that I believe in. Being politically engaged can come in many different forms: from political activism, environmental activism, community service, etc. To me, engaging in politics is engaging in thought provoking discussions and debates with many different perspectives and ideologies.”

Maya Johnson, FLC Senior | History and Psychology

“It’s almost like there is only political engagement, either you take an active role in shaping how our world ought to function, or you don’t. Are you gonna just sit back and let those decisions be made for you, or choose to get involved in that process? I choose to actively engage, no matter what that engagement looks like.”

Dawson Gipp, FLC Junior | Political Science, Philosophy, and Theatre

“For most of history individuals have been subject to the whims of powerful sovereign’s desires. This is not the case anymore for most, and that is because of the incredible work of many actors across the world all working to give us, the individuals, the power to determine our own future. If we do not use this gift given to us by our predecessors then their time on earth was wasted and surely ours will be as well.”

Elly Harder, FLC Senior | Economics

Maya Johnson, FLC Senior | History and Psychology

“It’s almost like there is only political engagement, either you take an active role in shaping how our world ought to function, or you don’t. Are you gonna just sit back and let those decisions be made for you, or choose to get involved in that process? I choose to actively engage, no matter what that engagement looks like.”

Dawson Gipp, FLC Junior | Political Science, Philosophy, and Theatre

“For most of history individuals have been subject to the whims of powerful sovereign’s desires. This is not the case anymore for most, and that is because of the incredible work of many actors across the world all working to give us, the individuals, the power to determine our own future. If we do not use this gift given to us by our predecessors then their time on earth was wasted and surely ours will be as well.”

Elly Harder, FLC Senior | Economics

Don’t forget to vote in the student government (ASFLC) elections, April 5-7!

https://stuelect.fortlewis.edu

https://stuelect.fortlewis.edu