Political Science Club Officers

PRESIDENT Jackson Berridge

VICE PRESIDENT Dawson Gipp

SECRETARY Benjamin Brewer

TREASURER Elly Harder

If you have any questions or concerns about this newsletter,

please contact Dr. Ruth Alminas at (970) 247-6166 or by email at [email protected].

PRESIDENT Jackson Berridge

VICE PRESIDENT Dawson Gipp

SECRETARY Benjamin Brewer

TREASURER Elly Harder

If you have any questions or concerns about this newsletter,

please contact Dr. Ruth Alminas at (970) 247-6166 or by email at [email protected].

Nuclear Deterrence and New Politics

By Elly Harder, Political Science Club Treasurer

Hello Fort Lewis students & staff and welcome to the Political Science club’s February newsletter! I hope that the start of everyone's semester has been going smoothly as we return from this lengthy winter break. In this article release Benjamin Brewer will be discussing whether or not nuclear weapons are required to maintain peace. It will dive into the intricacies of international relations between states and analyze the human cost for holding on to the past. It is sure to be an interesting read along with our other piece by Jackson Berridge which is asking a young political science major how he and others like him got interested in politics.

We also love talking politics with all of you so make sure to look out for a future meeting where we can discuss Ben’s article together! It is sure to bring up some thoughtful discussions so if you are interested in that make sure to keep up to date on our Fort Lewis app posts, and an ear open in your political science classes for a future date and location.

Hello Fort Lewis students & staff and welcome to the Political Science club’s February newsletter! I hope that the start of everyone's semester has been going smoothly as we return from this lengthy winter break. In this article release Benjamin Brewer will be discussing whether or not nuclear weapons are required to maintain peace. It will dive into the intricacies of international relations between states and analyze the human cost for holding on to the past. It is sure to be an interesting read along with our other piece by Jackson Berridge which is asking a young political science major how he and others like him got interested in politics.

We also love talking politics with all of you so make sure to look out for a future meeting where we can discuss Ben’s article together! It is sure to bring up some thoughtful discussions so if you are interested in that make sure to keep up to date on our Fort Lewis app posts, and an ear open in your political science classes for a future date and location.

Let’s Talk About It:

The Case for Nuclear Deterrence

By Benjamin F. Brewer, Political Science Club Secretary

Introduction

The thought of nuclear holocaust has haunted the public imagination since the United States decimated Nagasaki and Hiroshima 75 years ago, killing over 225,000 Japanese citizens -- which was followed by the end to the second world war. Indeed, images of scorched earth, flattened cities and charred shadows of human beings have been used in entertainment franchises for decades as a way to depict the fall of humanity (e.g. Fallout, Terminator, and Mad Max to name a few). In reality, however, nuclear weapons have been detonated in a theater of war only twice, and yet their frightening capacity for destruction has been the subject of a decades-long debate, “Do we need nuclear weapons?” The answer, I believe, is yes.

In this article, I posit that nuclear weapons, as terrifying as they may be, have kept the ‘Great Powers’ of the world in check. More specifically, I propose that the spread of nuclear arms to the nuclear-weapons states (NWS) have allowed the wider international community to both stabilize and avoid the horrors of conventional warfare. From this, I will conclude that nuclear weapons technology is here to stay.

Before I begin, however, I would like to preface my argument by stating that its main point is rested upon the assumption that these weapons are held by “rational state actors.” That is, governments that are both stabilized and able to effectively control their respective arsenals. In the hands of a non-rational actor, we can not expect nuclear weapons to be handled and maintained properly. However, I would argue that the holder of said weapon is not immune to the same cost-benefit analysis that is heavily influenced by the M.A.D. principle.

1. M.A.D.

“Mutually Assured Destruction” (known as the MAD doctrine) is crucial to understanding nuclear deterrence. Developed by Wilkie Collins and further shaped by George Brennan and Robert McNamara, mutually assured destruction is a “principle of deterrence founded on the notion that a nuclear attack by one superpower would be met with an overwhelming nuclear counterattack such that both the attacker and the defender would be annihilated.” Simply put, the M.A.D. doctrine assures that in a war between two nuclear states there are no winners.

2. The Benefits of M.A.D. & Alternative Explanations

Because of the M.A.D. doctrine, nuclear states have taken great care not to engage in open conflict. This is because these nuclear capable actors, like most human beings, are able to assess risk. In More May Be Better, Dr. Kenneth N. Waltz explains how nuclear capability reshapes the cost-benefit analysis of potential spoilers of peace.

“In a conventional world, a country can sensibly attack if it believes that success is possible. In a nuclear world, a would-be attacker is deterred if it believes that the attacker may retaliate. Uncertainty of response, not certainty, is required for deterrence because, if retaliation occurs, one may risk losing so much.”

In other words, the costs of nuclear retaliation far exceed even the greatest of benefits that could be gained through war. Thus, nuclear weapons have hung like the Sword of Damocles over international state actors -- guaranteeing peace by the threat of annihilation.

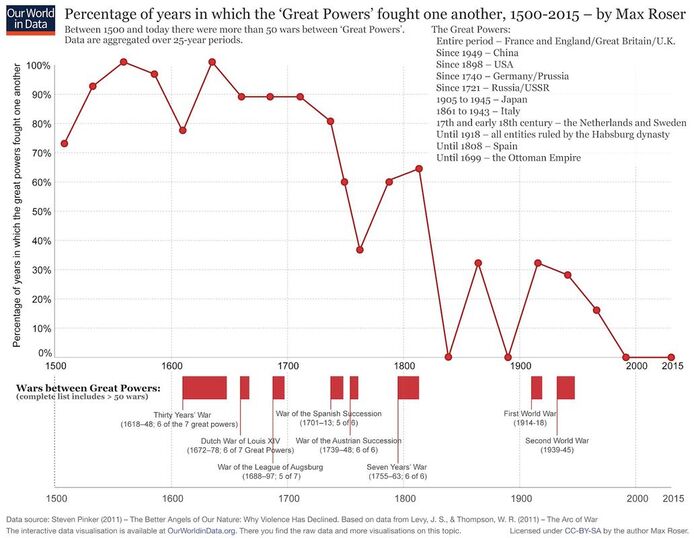

Interestingly enough, this guarantee has remained unbroken for several decades. As a matter of fact, there has been a downward trend in conflict between the Great Powers since the late 1940s -- with virtually no clashes in the last few decades.

Introduction

The thought of nuclear holocaust has haunted the public imagination since the United States decimated Nagasaki and Hiroshima 75 years ago, killing over 225,000 Japanese citizens -- which was followed by the end to the second world war. Indeed, images of scorched earth, flattened cities and charred shadows of human beings have been used in entertainment franchises for decades as a way to depict the fall of humanity (e.g. Fallout, Terminator, and Mad Max to name a few). In reality, however, nuclear weapons have been detonated in a theater of war only twice, and yet their frightening capacity for destruction has been the subject of a decades-long debate, “Do we need nuclear weapons?” The answer, I believe, is yes.

In this article, I posit that nuclear weapons, as terrifying as they may be, have kept the ‘Great Powers’ of the world in check. More specifically, I propose that the spread of nuclear arms to the nuclear-weapons states (NWS) have allowed the wider international community to both stabilize and avoid the horrors of conventional warfare. From this, I will conclude that nuclear weapons technology is here to stay.

Before I begin, however, I would like to preface my argument by stating that its main point is rested upon the assumption that these weapons are held by “rational state actors.” That is, governments that are both stabilized and able to effectively control their respective arsenals. In the hands of a non-rational actor, we can not expect nuclear weapons to be handled and maintained properly. However, I would argue that the holder of said weapon is not immune to the same cost-benefit analysis that is heavily influenced by the M.A.D. principle.

1. M.A.D.

“Mutually Assured Destruction” (known as the MAD doctrine) is crucial to understanding nuclear deterrence. Developed by Wilkie Collins and further shaped by George Brennan and Robert McNamara, mutually assured destruction is a “principle of deterrence founded on the notion that a nuclear attack by one superpower would be met with an overwhelming nuclear counterattack such that both the attacker and the defender would be annihilated.” Simply put, the M.A.D. doctrine assures that in a war between two nuclear states there are no winners.

2. The Benefits of M.A.D. & Alternative Explanations

Because of the M.A.D. doctrine, nuclear states have taken great care not to engage in open conflict. This is because these nuclear capable actors, like most human beings, are able to assess risk. In More May Be Better, Dr. Kenneth N. Waltz explains how nuclear capability reshapes the cost-benefit analysis of potential spoilers of peace.

“In a conventional world, a country can sensibly attack if it believes that success is possible. In a nuclear world, a would-be attacker is deterred if it believes that the attacker may retaliate. Uncertainty of response, not certainty, is required for deterrence because, if retaliation occurs, one may risk losing so much.”

In other words, the costs of nuclear retaliation far exceed even the greatest of benefits that could be gained through war. Thus, nuclear weapons have hung like the Sword of Damocles over international state actors -- guaranteeing peace by the threat of annihilation.

Interestingly enough, this guarantee has remained unbroken for several decades. As a matter of fact, there has been a downward trend in conflict between the Great Powers since the late 1940s -- with virtually no clashes in the last few decades.

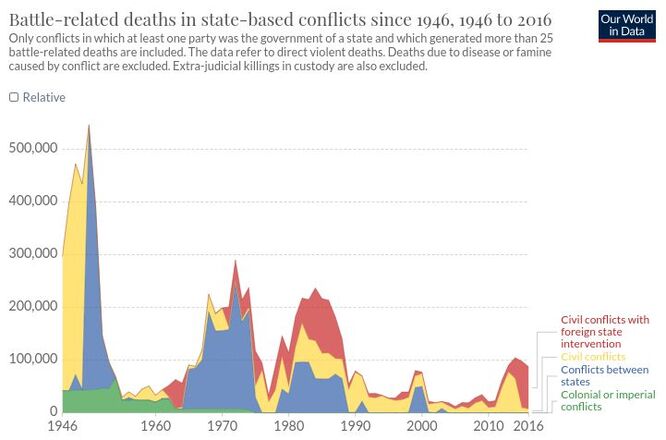

Additionally, battle-related deaths have also sharply decreased since the end of WWII.

Indeed, it seems that the advent of nuclear weapons has produced a measurable effect of international peace.

However, some may attribute this to the ‘Trade-Peace’ liberal theory which assumes, inter alia, that “an increase in trade leads to universal benefits (which expands to include world peace).” I find this unconvincing. This is because, historically, there have been free-trade economic systems in place that were eventually plagued by war. For example, one need only look at Great Britain prior to 1914 to see that their free-trade policies did little to postpone or mitigate the Great War that erupted across Europe.

In fact, many market liberals, including Adam Smith in Wealth of Nations, had their doubts about the pacifying effect of trade.

“Nations have been taught that their interest consisted in beggaring all their neighbours. Each nation has been made to look with an invidious eye upon the prosperity of all the nations with which it trades, and to consider their gain as its own loss. Commerce, which ought naturally to be, among nations, as among individuals, a bond of union and friendship, has become the most fertile source of discord and animosity.”

It could be argued that free-trade is not the great equalizer that it is lauded to be. To quote Dr. Richard Ebeling, “free-trade cannot prevent war when men no longer believe in peace.” With the proliferation of nuclear weapons, I argue that mankind is compelled to believe in peace. This is because the alternative, again, is mutually assured destruction. However, I will concede that the free movement of both goods and capital may certainly facilitate peace -- but that it does not guarantee it. Despite this, certain circles in the international community advocate against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. However, what would a world without nuclear arms look like?

3. Could we Do Without the Bomb?

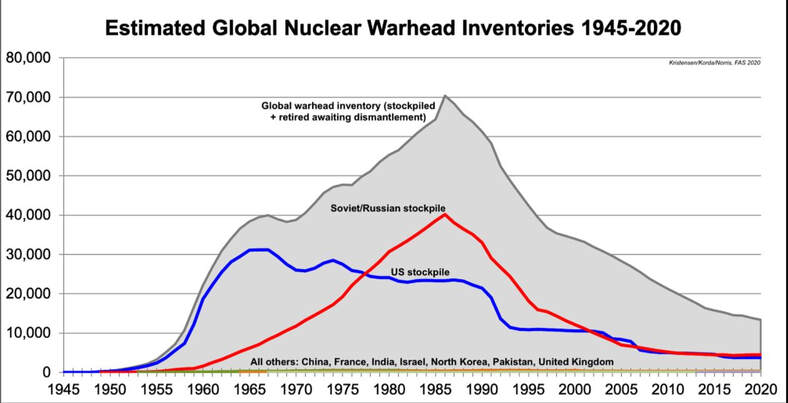

Since 1970, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) has encouraged its NWS parties (i.e. France, United Kingdom, the United States, Russia, and China) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” As a result, nuclear arsenals around the world have effectively been reduced from 70,000 in the 1980s to 14,200 in 2018. Despite this, all NWS plan to maintain a nuclear deterrent in some form -- with China slowly increasing its arsenal.

However, some may attribute this to the ‘Trade-Peace’ liberal theory which assumes, inter alia, that “an increase in trade leads to universal benefits (which expands to include world peace).” I find this unconvincing. This is because, historically, there have been free-trade economic systems in place that were eventually plagued by war. For example, one need only look at Great Britain prior to 1914 to see that their free-trade policies did little to postpone or mitigate the Great War that erupted across Europe.

In fact, many market liberals, including Adam Smith in Wealth of Nations, had their doubts about the pacifying effect of trade.

“Nations have been taught that their interest consisted in beggaring all their neighbours. Each nation has been made to look with an invidious eye upon the prosperity of all the nations with which it trades, and to consider their gain as its own loss. Commerce, which ought naturally to be, among nations, as among individuals, a bond of union and friendship, has become the most fertile source of discord and animosity.”

It could be argued that free-trade is not the great equalizer that it is lauded to be. To quote Dr. Richard Ebeling, “free-trade cannot prevent war when men no longer believe in peace.” With the proliferation of nuclear weapons, I argue that mankind is compelled to believe in peace. This is because the alternative, again, is mutually assured destruction. However, I will concede that the free movement of both goods and capital may certainly facilitate peace -- but that it does not guarantee it. Despite this, certain circles in the international community advocate against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. However, what would a world without nuclear arms look like?

3. Could we Do Without the Bomb?

Since 1970, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) has encouraged its NWS parties (i.e. France, United Kingdom, the United States, Russia, and China) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” As a result, nuclear arsenals around the world have effectively been reduced from 70,000 in the 1980s to 14,200 in 2018. Despite this, all NWS plan to maintain a nuclear deterrent in some form -- with China slowly increasing its arsenal.

The above reductions (but not complete relinquishment) of nuclear arms seems to indicate that while the NWS acknowledge that tens of thousands of nuclear weapons are unnecessary, they also understand that there needs to be enough in possession to constitute a credible threat of retaliation (CTR). Without CTR (or allies that provide similar insurance), a state opens itself up to attack without the ability to retaliate proportionally. Complete disarmament, it seems, would quickly devolve into a game of “you first.”

However, let us suppose that complete disarmament is both rational as well as possible. In A World Without Nuclear Weapons?, Dr. Thomas Schelling argues that former NWS could rebuild their arsenals just as quickly as they dismantled them.

“A “world without nuclear weapons” would be a world in which the United States, Russia, Israel, China, and half a dozen or a dozen other countries would have hair-trigger mobilization plans to rebuild nuclear weapons and mobilize or commandeer delivery systems, and would have prepared targets to preempt other nations’ nuclear facilities, all in a high-alert status, with practice drills and secure emergency communications. Every crisis would be a nuclear crisis, any war could become a nuclear war. The urge to preempt would dominate; whoever gets the first few weapons will coerce or preempt. It would be a nervous world.”

The puzzle proposed by Schelling is daunting, to say the least. Even if the international community rid the world of nuclear weapons, they could always return in force when convenient.

4. A Nuclear World

In truth, the idea of nuclear weapons will never completely disappear from the world. Ideas, unlike material things (e.g. land, buildings, and possessions) cannot be destroyed so easily. Moreover, as long as the idea of a nuclear weapon exists, I argue then that its physical counterpart will always return somewhere -- in the hands of somebody. I would rather maintain the status quo of nuclear weapons being in the hands of multiple state actors in a multipolar political landscape. This is because the more horizontally spread out these weapons of mass destruction are, the harder it is for state actors to conduct that aforementioned cost-benefit analysis for their use.

Ultimately, I believe the world is a safer place than it was prior to the invention of the nuclear weapon. With it, our generation (and those before us) have never been tasked with fighting in a major conflict between global superpowers. As Waltz puts it, “Limiting wars in a conventional world has proved difficult. In a nuclear world, only limited wars can be fought.” Indeed, images of a nuclear holocaust are chilling, but it could be argued that conventional wars are just as horrific. In all truth, the human race was constantly engaged in conventional global wars on a regular basis before the bomb was invented, but we have only experienced nuclear detonation twice. Because of this, I think we should accept the reality of a nuclear peace

Bibliography

Ebelin, Richard M. “Can Free Trade Really Prevent War?” Mises Institute. Ludwig Von Mises Institute, March 18, 2002. https://mises.org/library/can-free-trade-really-prevent-war.

“Hiroshima and NAGASAKI Death Toll,” October 10, 2007. http://www.aasc.ucla.edu/cab/200708230009.html.

Kimball, Daryl. “The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) at a Glance.” Arms Control Association, March 2020. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/nptfact.

Kristensen, Hans M, and Matt Korda. “Status of World Nuclear Forces.” Federation Of American Scientists, September 2020. https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/.

“Nuclear Disarmament Resource Collection.” Nuclear Threat Initiative - Ten Years of Building a Safer World. Nuclear Threat Initiative, December 15, 2020. https://www.nti.org/analysis/reports/nuclear-disarmament/.

Ray, Micheal. “Mutual Assured Destruction.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., July 17, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mutual-assured-destruction.

Roser, Max. “War and Peace.” Our World in Data, December 13, 2016. https://ourworldindata.org/war-and-peace#percentage-of-years-in-which-the-great-powers-fought-one-another-1500-2015-max-roser-ref.

Schelling, Thomas C. “A World without Nuclear Weapons?” Dædalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 2009. https://www.amacad.org/publication/world-without-nuclear-weapons#:~:text=In%20summary%2C%20a%20%E2%80%9Cworld%20without,have%20prepared%20targets%20to%20preempt.

Smith, Adam. Wealth of Nations. London, UK: J.M. Dent & Sons, Limited, 1910.

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) – UNODA.” United Nations Office For Disarmament Affairs. United Nations . Accessed February 15, 2021. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text/#:~:text=Article%20VI,strict%20and%20effective%20international%20control.

Waltz, Kenneth N. The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better. London, UK: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1981.

Ebelin, Richard M. “Can Free Trade Really Prevent War?” Mises Institute. Ludwig Von Mises Institute, March 18, 2002. https://mises.org/library/can-free-trade-really-prevent-war.

“Hiroshima and NAGASAKI Death Toll,” October 10, 2007. http://www.aasc.ucla.edu/cab/200708230009.html.

Kimball, Daryl. “The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) at a Glance.” Arms Control Association, March 2020. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/nptfact.

Kristensen, Hans M, and Matt Korda. “Status of World Nuclear Forces.” Federation Of American Scientists, September 2020. https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/.

“Nuclear Disarmament Resource Collection.” Nuclear Threat Initiative - Ten Years of Building a Safer World. Nuclear Threat Initiative, December 15, 2020. https://www.nti.org/analysis/reports/nuclear-disarmament/.

Ray, Micheal. “Mutual Assured Destruction.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., July 17, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mutual-assured-destruction.

Roser, Max. “War and Peace.” Our World in Data, December 13, 2016. https://ourworldindata.org/war-and-peace#percentage-of-years-in-which-the-great-powers-fought-one-another-1500-2015-max-roser-ref.

Schelling, Thomas C. “A World without Nuclear Weapons?” Dædalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 2009. https://www.amacad.org/publication/world-without-nuclear-weapons#:~:text=In%20summary%2C%20a%20%E2%80%9Cworld%20without,have%20prepared%20targets%20to%20preempt.

Smith, Adam. Wealth of Nations. London, UK: J.M. Dent & Sons, Limited, 1910.

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) – UNODA.” United Nations Office For Disarmament Affairs. United Nations . Accessed February 15, 2021. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text/#:~:text=Article%20VI,strict%20and%20effective%20international%20control.

Waltz, Kenneth N. The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better. London, UK: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1981.

Let's Continue the Discussion!

This semester, the Political Science Club would like to invite the FLC community to participate in a series of discussions about hot-button issues in the classroom and beyond. Our goal is to practice creating safe environments for constructive dialogue across a wide variety of differing perspectives. Above all, we ask that as you join us in this conversation, you do not try to “win” the conversation. This is not a competition. We are all here to listen and learn. To make sure we can create the conditions for constructive dialogue, we ask that you please read and comply with the following ground rules.

Ground Rules for Discussion

The Political Science Club and all of our events are open to any FLC students who are interested in political engagement and civil discourse. If you cannot not abide by these ground rules, we will ask you to remove yourself from the conversation until you can.

- Be authentic and honest.

- Listen (or read) carefully, especially if you disagree. Do not formulate a response until you have first taken the time to understand what is being communicated.

- Ask questions to help you understand perspectives different from your own.

- Be respectful when asking for evidence supporting a statement that has been made.

- Don’t assume anything about one another’s beliefs, ideas or identities.

- Don’t make generalizations about any group of people. Don’t use the words ‘always’ or ‘never’.

- Recognize the difference between facts and opinions. Both are legitimate when expressed appropriately, but we need to be careful not to confuse the two.

- Keep an open mind and remember that we are here to learn from each other and solve shared problems rather than to convince or win arguments.

- Be patient with one another and ourselves in cases of low knowledge or awareness, remembering that our intention is to learn from each other.

- Acknowledge intent and address impact. Assume that others are speaking and acting from a place of good intent. At the same time, if our actions negatively impact others, we must address, understand, and take responsibility for that impact.

- Practice inclusivity and appreciate diversity of the identities, perspectives, and experiences in our community.

FLC Student Spotlight on Travis Carlson

By Jackson Berridge, Political Science Club President

These last few years have seemed unreal. New policies have been thrown around left and right, and the ‘pandemic effect’ has heightened our awareness in this country of our democratic values, our business practices, environmental issues, civic contribution efforts, and the disconnect between Washington and Citizens. The prospect of meaningful democratic participation is now in question.

Travis Carlson is a new Political Science student at Fort Lewis College, and has come here to learn how Washington affects our lives and what he can do to effect change himself. I asked Travis what made him, a 24 year old, become interested in politics recently: “I guess it was the government’s lack of response to the coronavirus and I realized that policy decisions have a pretty big impact on our lives. Before this I didn’t think it mattered… I didn’t really care.”

Travis considers himself to be part of a group that has become interested in becoming “politically engaged” because of how involved politics has become with everyone’s lives recently. “Things like the BLM movements and the government’s response to Coronavirus made me wonder how I can make positive change. I want to understand how our institutions work, why they work that way, and examine how I can change that.” I asked Travis if the FLC Political Science curriculum and the courses he is taking in general have met those expectations: “Yeah I think so. It’s kind of just basics right now I feel, but this is something I find so engaging. More than anything I have before.” As a fellow Political Science student who felt disillusioned by the state of our country and the world and saw contemporary politics as bearing a significant amount of responsibility for that disillusionment, I can understand the frustration. That is why Travis and many others came to Fort Lewis College to study Political Science. From Travis: “Just like I said earlier, I really do believe that policy influences our lives materially … Everything is politicized.”

These last few years have seemed unreal. New policies have been thrown around left and right, and the ‘pandemic effect’ has heightened our awareness in this country of our democratic values, our business practices, environmental issues, civic contribution efforts, and the disconnect between Washington and Citizens. The prospect of meaningful democratic participation is now in question.

Travis Carlson is a new Political Science student at Fort Lewis College, and has come here to learn how Washington affects our lives and what he can do to effect change himself. I asked Travis what made him, a 24 year old, become interested in politics recently: “I guess it was the government’s lack of response to the coronavirus and I realized that policy decisions have a pretty big impact on our lives. Before this I didn’t think it mattered… I didn’t really care.”

Travis considers himself to be part of a group that has become interested in becoming “politically engaged” because of how involved politics has become with everyone’s lives recently. “Things like the BLM movements and the government’s response to Coronavirus made me wonder how I can make positive change. I want to understand how our institutions work, why they work that way, and examine how I can change that.” I asked Travis if the FLC Political Science curriculum and the courses he is taking in general have met those expectations: “Yeah I think so. It’s kind of just basics right now I feel, but this is something I find so engaging. More than anything I have before.” As a fellow Political Science student who felt disillusioned by the state of our country and the world and saw contemporary politics as bearing a significant amount of responsibility for that disillusionment, I can understand the frustration. That is why Travis and many others came to Fort Lewis College to study Political Science. From Travis: “Just like I said earlier, I really do believe that policy influences our lives materially … Everything is politicized.”

Why is Political Engagement Important to You?

“Meaningful political engagement includes voting, yes, but also organizing, joining social movements, making your voice heard! When I look around, I see many injustices in need of redress and institutional failures in need of repair, and I believe that our best chance at changing things for the better comes through political engagement. When we look at our history and see the improvements that have been made over time in our own nation and beyond, they have always resulted from the engagement of the people, not from the beneficence of the leadership.”

Dr. Ruth Alminas, Assistant Professor of Political Science

“I believe everyone should be politically engaged. And to me, that means more than just voting. Being politically active can range from voting to participating in a campaign to canvassing to @'ing a politician on Twitter. All of that is important because collective political engagement is the first step to improving the lives and material conditions of this country's underserved citizens. I want to learn how I can play a role in increasing political engagement. I want our populace to demand more from our government.”

Travis Carlson, FLC Political Science Student

“Political engagement means more than simply paying attention to the news during election cycles. The 2020 elections are over but there is still so much we can do as democratic citizens to participate civically. We still need to hold our government accountable. We still need to watch what our government does closely and see how well it matches up with our everyday experiences in this country and be a voice for and in our communities. A new administration in Washington is not a guarantee that our lives around us will change for the better, in part because there are still significant issues that our government can not tackle without the help of its citizens.

We still need to watch over our community and be mindful of how we can change it. There is always something going on near you that you can help with. There are non-profit organizations in your area, there are county and city-level government projects that can always use a hand to help those in need. There are issues around you and further away that if you see, and take issue with, you can take action on, whether that means calling your local and at-large representatives, getting involved personally, or organizing your own support structures to address issues you care about. Our political engagement will always be important because the citizen is the heart of our democracy, and it is us who bear the consequences of our own negligence, not Washington.”

Jackson Berridge, Political Science Club President

Dr. Ruth Alminas, Assistant Professor of Political Science

“I believe everyone should be politically engaged. And to me, that means more than just voting. Being politically active can range from voting to participating in a campaign to canvassing to @'ing a politician on Twitter. All of that is important because collective political engagement is the first step to improving the lives and material conditions of this country's underserved citizens. I want to learn how I can play a role in increasing political engagement. I want our populace to demand more from our government.”

Travis Carlson, FLC Political Science Student

“Political engagement means more than simply paying attention to the news during election cycles. The 2020 elections are over but there is still so much we can do as democratic citizens to participate civically. We still need to hold our government accountable. We still need to watch what our government does closely and see how well it matches up with our everyday experiences in this country and be a voice for and in our communities. A new administration in Washington is not a guarantee that our lives around us will change for the better, in part because there are still significant issues that our government can not tackle without the help of its citizens.

We still need to watch over our community and be mindful of how we can change it. There is always something going on near you that you can help with. There are non-profit organizations in your area, there are county and city-level government projects that can always use a hand to help those in need. There are issues around you and further away that if you see, and take issue with, you can take action on, whether that means calling your local and at-large representatives, getting involved personally, or organizing your own support structures to address issues you care about. Our political engagement will always be important because the citizen is the heart of our democracy, and it is us who bear the consequences of our own negligence, not Washington.”

Jackson Berridge, Political Science Club President