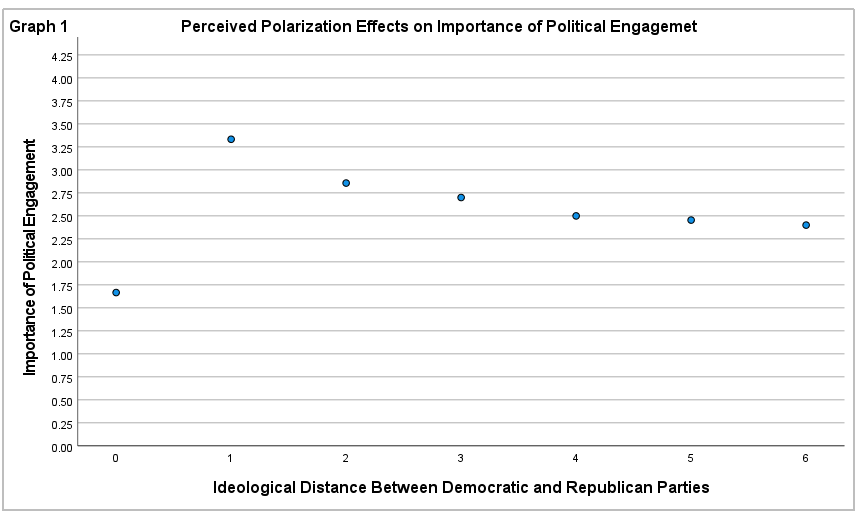

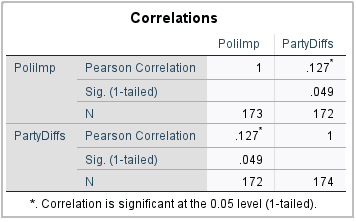

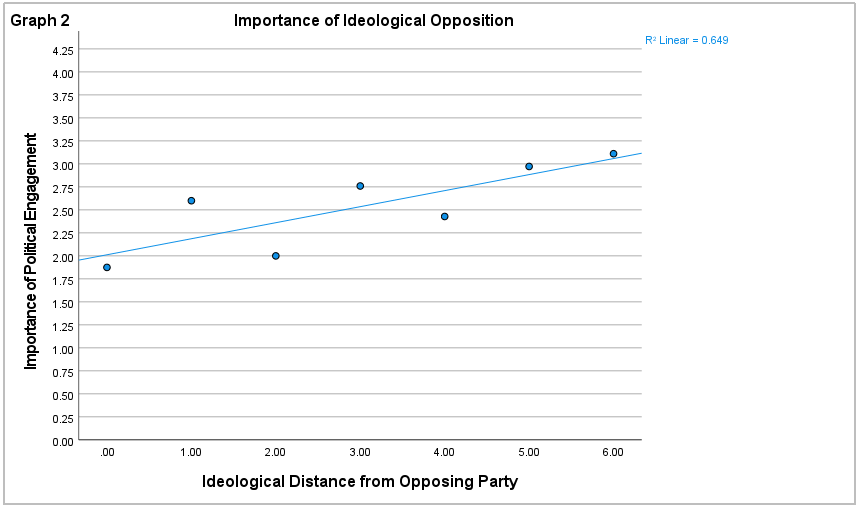

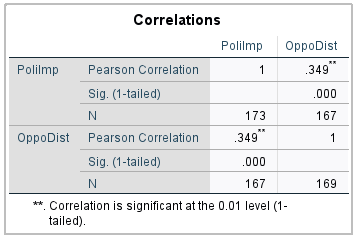

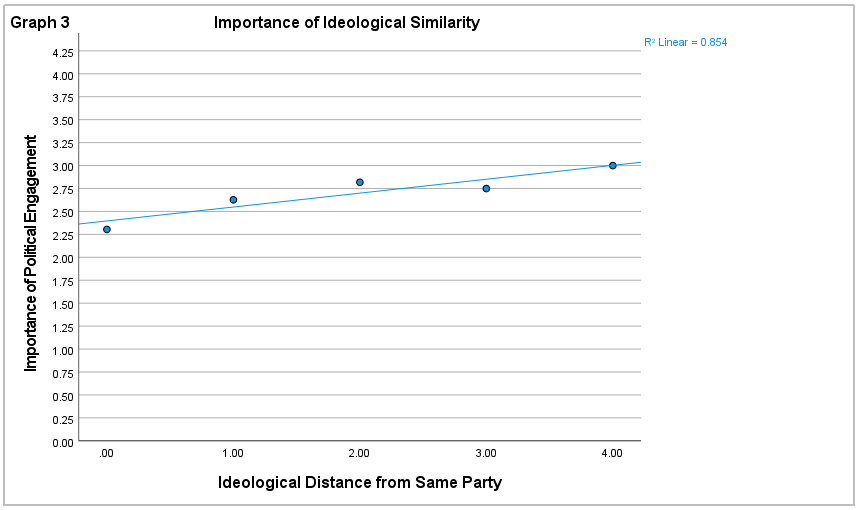

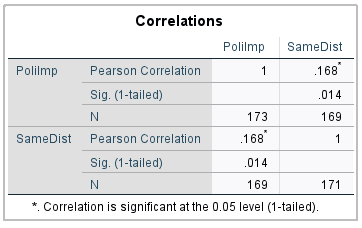

Ideological Polarization and its affects on Political Engagement By Jackson Berridge & Bryce York11/16/2020 Introduction Polarization in United States politics is perhaps the most salient feature of the US political climate today. This is an important issue as that climate is not only characterized by significant polarization, but by significant ideological consequence That volatile climate exists within a democratic context where political engagement on the part of the citizen is absolutely essential. This study looks at two potential fallouts of that polarization and ideological consequence as it may affect an individual’s likelihood to think that getting involved in politics is important. The survey in which the data for this study was collected took place the week before November 3rd, 2020 – the presidential election where more voters turned out than any other election in US history. Being involved in politics is about much more than just voting, but if more people voted during the 2020 US presidential election than ever before in history, and if the two parties and the citizens of the US are possibly as polarized as they have ever been, then maybe there is a relationship there. This study was conducted using data collected from Fort Lewis College (FLC), which is a relatively small Liberal Arts college in southwest Colorado. These results then are not emblematic of the entire US population, but they do tell an impactful and important story none the less. The questions were: How does perceived ideological polarization of the Democratic and Republican parties affect how important an FLC student sees getting involved in politics as being? How does an FLC student’s perceived ideological distance from the opposing ideological party influence how important it is for them to get involved in politics? The hypotheses were:H1: Increased levels of perceived ideological polarization between the Democratic and Republican parties increases how important it is for an FLC student to get involved in politics. H2: Increased magnitude of perceived ideological distance from the ideologically opposed major political party increases how important it is for an FLC student to get involved in politics. H1 background: The study “Elite polarization and mass political engagement: Information, alienation, and mobilization” by Jae M. Lee [1] looks at mass alienation and mobilization as factors of how people with different levels of education behave in political situations. Lee uses the ANES survey (1972-2004) to conduct his study similarly to how this FLC study will be using and applying this data to find different results of importance of political involvement and polarization. Lee fins that “where parties have distinct ideological platforms [they] tend to display more connections between voters' left-right positions and their vote.” [2]This FLC study uses the same questions taken from the ANES survey to measure perceived ideological measurements of the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as a similar question to political engagement. Instead of measuring political engagement through voting behavior, it is a measurement of how important it is for a respondent to personally be involved in politics. Our second hypothesis looks more at the effects of left-right placement and voting tendencies discussed in Lee’s article, whereas our first hypothesis pertains to the effects of polarization on pure political engagement itself. “The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems: Party System Polarization, Its Measurement, and Its Consequences” (by Russel J. Dalton [3] argues that numerous differentiating ideals have less of an impact on civic engagement than polarization. The author also claims that the most important piece of the puzzle is the quality of the existing competition between parties. Dalton works to show us why our political parties became polarized and he uses the power behind polarization as a predictor for voter turnout. Dalton argues that polarization between parties can increase their support by creating a rival with another competitive party, thus creating a party system with less options but more support. This FLC study, and testing the first hypothesis in particular, looks at the impact of how ideologically polarized parties are (as perceived by a respondent) might be affecting how important it is to the respondent for them to be politically engaged. H2 background: In addition to the article “Elite polarization and mass political engagement: Information, alienation, and mobilization,” the second hypothesis of this FLC study rests some inception on ideas presented in the article “Reassessing Proximity Voting: Expertise, Party, and Choice in Congressional Elections” by Danielle A. Joesten and Walter J. Stone. [4] This article leads to a different idea of how ideological party polarization may affect the likelihood of an individual to be politically engaged – how the ideology of a party relates to the individual, not an opposing party. What they find is that “voter distance from the … ideological cut point … are associated with enhanced levels of … voting.” [5]The second hypothesis in this study tests a similar question – how the ideological cut point of a party (not a candidate) may affect a citizen’s view of the importance of being politically engaged themselves (not likelihood to vote as the Joesten and Walter study uses). A third study which our second hypothesis draws similarities to is “Ideological Voting in 1980 Republican Presidential Primaries” [6] by Mark J. Wattier. Wattier tests whether someone is more likely to vote for a candidate whom they are ideologically close to. Included in the test of the second hypothesis is a juxtaposition with a respondent’s view of how important it is for them to be politically engaged as it is affected by the magnitude of how ideologically similar they see themselves being to their associated ideological party. Wattier finds that “when primary voters perceived a difference in candidate ideologies, they usually supported the candidate closer to their own ideology.” [7] This FLC study operates with a similar difference in measurements to the studies germane to the first hypothesis and the first hypothesis test itself, so it does not necessarily correlate with Wattier’s, as this FLC study will not be looking at voting tendencies but rather personal importance of being politically engaged. FLC Engagement Study assumptions, methodology, and measurements: |

|